By Kiel Porter and Loren Grush, Bloomberg Businessweek

Compiled by: Luffy, Foresight News

Jed McCaleb has made a killing in cryptocurrency, and now he's ready to invest a large portion of it into his dream of going into space.

The billionaire founder of the infamous bitcoin exchange Mt. Gox and the cryptocurrency XRP is single-handedly funding an ambitious plan: building the world's first commercial space station and sending it into space.

If successful, his startup, Vast Space LLC, is expected to win a potentially multibillion-dollar contract from NASA next year to replace the International Space Station. If unsuccessful, McCaleb said he is prepared to lose $1 billion. As of the end of 2023, McCaleb controls billions of dollars in assets through two foundations, all of which come from his personal donations.

“This is a critical step toward a future where humans can live off-Earth,” McCaleb, 50, said at the company’s headquarters in Long Beach, California. “Not many people are willing to commit the resources, time and risk that I have.”

He has since hired an industry veteran as CEO, and SpaceX is providing some of its technology to Vast. At the same time, Elon Musk has urged the United States to accelerate the retirement timeline of the International Space Station, which is currently scheduled to be retired at the end of 2030. Vast was founded in 2021, and some components of its spacecraft use technology developed by SpaceX, specifically the docking adapter used to connect the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft to the Vast space station, and the space internet system that provides Wi-Fi to the space station through Starlink. Vast has booked SpaceX's launch services to send its hardware into orbit and send astronauts to the space station, and SpaceX has also agreed to transport astronauts for Vast as long as NASA approves it.

Still, the task was daunting, and it was hard to see McCaleb as the man for it. A boy from an Arkansas farm and a UC Berkeley dropout with no background in aerospace, his career had been marked by getting first in emerging technologies and pivoting before government regulation and other headwinds upended them, a short-term mindset that seemed antithetical to the long-term focus needed to win a high-stakes race to create a technological miracle.

Vast's headquarters in Long Beach. Source: Bloomberg Businessweek

Sam Yagan, a friend of McCaleb’s who co-founded an online file-sharing company more than two decades ago, said the entrepreneur is a thoughtful risk-taker. “He’s very rational about these things,” Yagan said, “but he’s willing to take what you and I would consider big risks, which is a bit of a maverick.”

Many Vast employees worked at SpaceX. The parking lot at the company’s headquarters is filled with cars made by Musk’s Tesla. One of the Cybertrucks belongs to Max Haot, who joined Vast in 2023 after McCaleb acquired his company. Haot has since become Vast’s CEO, having McCaleb (who drives a more modest Model 3) fly in once a week from his home in San Francisco to oversee the project.

Before being acquired, Haot did not focus on the space station field. Instead, he tried to emulate Musk and founded another rocket launch startup, Launcher. The company received $30 million in investment and made progress in developing rocket engines and vehicles, but the two satellites built by Launcher both suffered failures after entering space. In 2022, Haot met McCaleb while looking for investors.

McCaleb made the acquisition proposal with the stipulation that Haot would serve as Vast's president and eventually CEO. Haot was initially reluctant to accept the deal, but changed his mind when he realized that Launcher was having trouble getting the funding it needed.

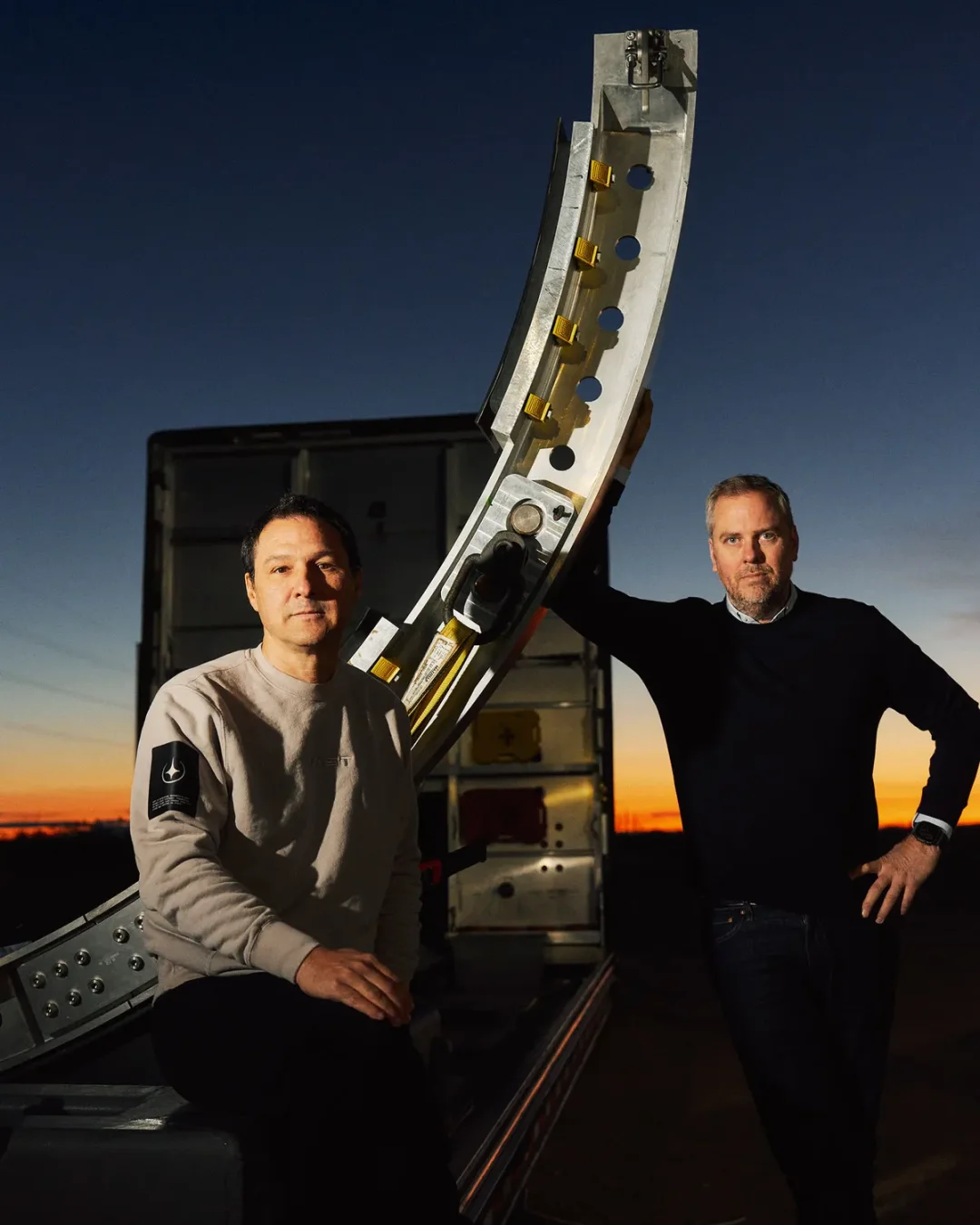

Vast founder and chairman Jed McCaleb and CEO Max Haot at the test site in Mojave, California. Source: Bloomberg Businessweek

Vast's grand vision goes beyond building the first private space station. The company also wants to develop an artificial gravity system to simulate Earth's environment for future astronauts. This is a complex undertaking that would require the use of centrifugal force and the placement of a huge rotating module in space. This is an attractive proposition because human experience living and working for a long time on the International Space Station has shown that long-term exposure to microgravity can damage various biological systems.

However, these are still far away. Currently, Vast needs to get its first space station into orbit. The company's staff has rapidly increased from less than 200 a year ago to 740, covering all kinds of talents from technical engineers to space suit manufacturers. Vast's headquarters operates 24 hours a day, and engineers and construction workers work in shifts, either expanding the Long Beach facility or building Vast's first prototype space station "Haven-1".

Space stations are a common element in pop culture, such as the Death Star in Star Wars and the eponymous space station in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. They have also been an important part of American space exploration since astronauts first boarded the experimental Skylab in 1973. Decades later, as the Cold War ended, NASA worked with Russia and other countries to build the larger International Space Station. Since November 2000, there has always been at least one astronaut on the International Space Station, who often study how materials and the human body behave in a microgravity environment.

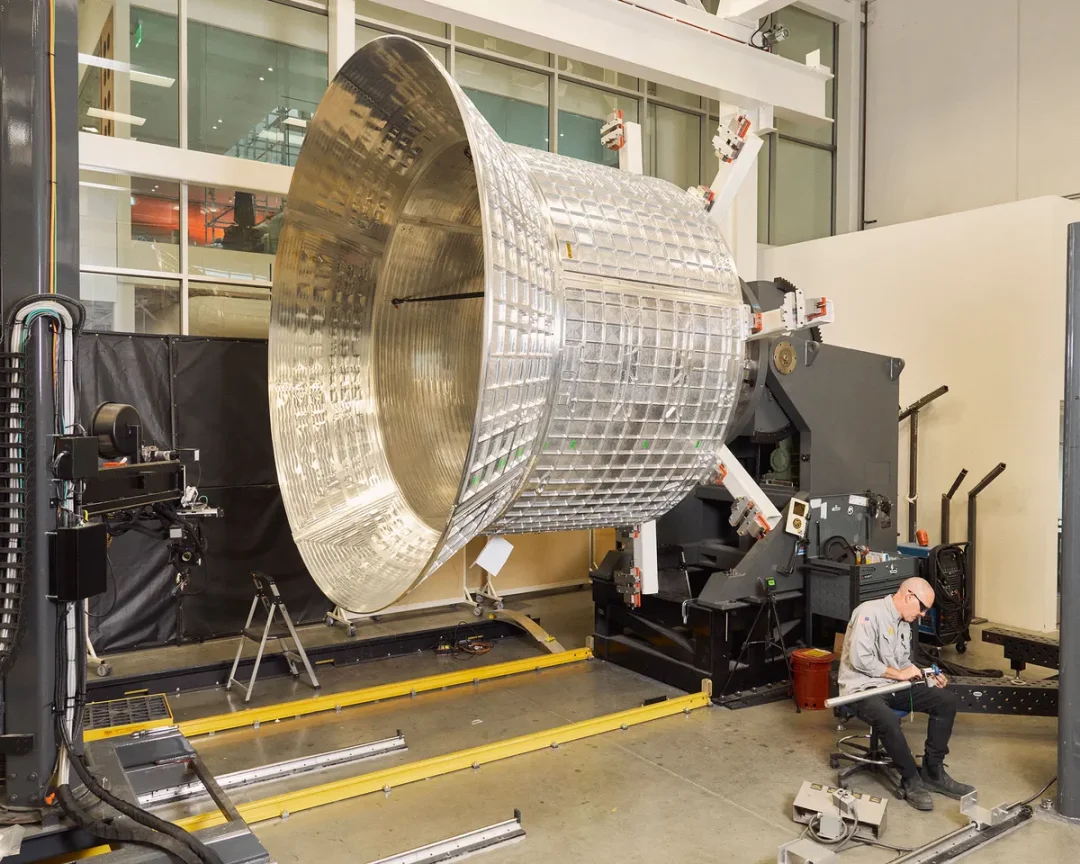

A technician at Vast headquarters. Source: Bloomberg Businessweek

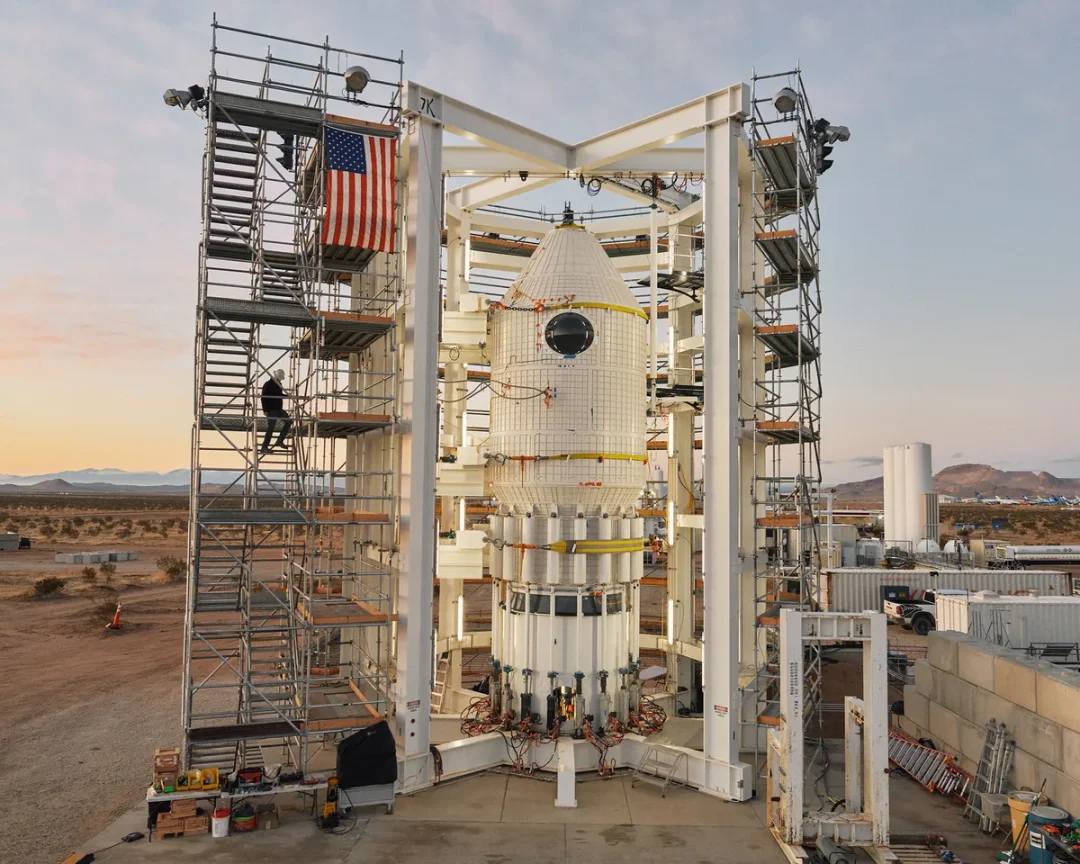

Haven-1 will be about 33 feet tall and 14.5 feet wide, and is designed to fit snugly inside the nose cone of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. The station will have about 1,600 cubic feet of habitable space, about twice the size of an average RV. It will feature private sleeping pods, a large window, wood paneling and a table for four people.

At least that’s its goal. In January, the company began building Haven-1, which is scheduled to launch in May 2026, a delay from its original August launch date. The company recently tested a prototype to confirm that its structure can withstand the internal air pressure, and is developing the power system, propulsion, and other key components for manned missions. Its shell must be able to withstand the harsh environment and temperatures of space while maintaining the air pressure and gases that humans are accustomed to on Earth.

“We are not a true space station company yet,” Haot said. “We are an aspiring space station company.”

The main structure of Haven-1 awaits further testing at Vast's Mojave base. Source: Bloomberg Businessweek

Assuming all goes well, after Haven-1 launches, Vast will launch four astronauts aboard a Falcon 9 rocket to dock with the space station. If the first launch is successful, Vast plans to launch the first module of the next space station, Haven-2, by 2028. It will be the starting point for a much larger base designed to replace NASA's International Space Station.

One of the biggest challenges will be creating an effective life support system. The International Space Station uses a regeneration system that recycles all wastewater into drinking water and converts carbon dioxide into breathable oxygen. Such a system is necessary if passengers are to stay on the station for an extended period of time, but Haven-1 will not have it, as astronauts are expected to stay only briefly. Vast plans to eventually equip Haven-2 with such a system, but the station is not expected to be manned for a long time in the first few years.

Rivals including Axiom Space, Blue Origin and Voyager Space Holdings are also racing to build their own space stations, but one advantage Vast has is McCaleb’s willingness to invest heavily in the project. “Vast is the only company that’s predominantly self-funded and ready to go,” says Chad Anderson, founder and managing partner of Space Capital, an investment firm focused on the space industry. “They’re an interesting choice in that regard.” (Anderson has no financial ties to Vast but has invested in SpaceX.)

While those competitors have aerospace backgrounds and some launch contracts, they don’t have such a close partnership with SpaceX.

Engineers work on life support systems in a clean room at Vast headquarters. Source: Bloomberg Businessweek

McCaleb is eager to downplay any personal relationship, saying he’s met Musk “a few times and he probably doesn’t remember me,” though both have invested in OpenAI. Despite their differences in approach and demeanor, their respective interests and unconventional paths to riches have many similarities: Both dropped out of school (Musk later), founded software businesses in emerging fields, and parlayed their love of fantasy and gaming into financial success.

McCaleb's first project, eDonkey, was one of the earliest file-sharing services on the Internet and an early competitor to Napster. The company was founded in 2000 and allowed users to share music and movies for free, bringing in millions of dollars a year through advertising. In 2006, the company closed down after agreeing to pay $30 million to the Recording Industry Association of America to avoid a copyright infringement lawsuit.

McCaleb's next success was Mt. Gox, one of the world's first bitcoin trading platforms. The site was founded by McCaleb in 2010, and a year later he sold a majority stake for an undisclosed price. In February 2014, the exchange went bankrupt, and users lost more than $400 million worth of bitcoin at the time, making it the largest cryptocurrency disaster in history before FTX collapsed in 2023. Although McCaleb remained a minority shareholder, he was not sanctioned and said he also suffered losses in the disaster.

By then, McCaleb had already moved on to his next project: XRP, the cryptocurrency on the Ripple protocol, which he also co-founded. McCaleb initially owned 9% of XRP. He left the company in 2013 after a disagreement with his co-founders, but kept his XRP and gradually sold it over the following years. During the cryptocurrency boom in late 2017, XRP's value soared, eventually swelling to a market value of $130 billion in January 2018, according to an analysis by XRPScan. McCaleb netted about $3.2 billion from the sale of XRP and Ripple shares between 2014 and 2022.

“He’s one of the 10 most important founders in the cryptocurrency space, even though few people really know him,” said Nic Carter, founding partner of Castle Island Ventures, an investment firm focused on public blockchains. “What’s interesting is that most of the other important people are the flamboyant, high-profile, and extravagant people.”

Despite his success, McCaleb maintains a small social circle, working mostly with Yagan and other longtime partners, and has a house in surfing hotspot Costa Rica, a home in Berkeley and his own private jet.

McCaleb provides a steady source of investment in an often volatile sector of the aerospace industry, where once-promising startups often fail due to lack of funding. Despite a lawsuit filed by a former employee alleging that Vast tried to cut corners, the company does not appear to have the same negative press as SpaceX. Its billionaire CEO spends most of his time at home with his wife and three children instead of trying to fight the federal government.

Haven-1's test facility at Vast. Source: Bloomberg Businessweek

If McCaleb's plan pans out, Vast has booked multiple crewed missions with SpaceX to send astronauts into orbit, and both McCaleb and Haot say they'd love to take those flights themselves. "As a kid, I spent a lot of time outdoors exploring, looking up at the sky and marveling at how amazing it is," McCaleb says. But it all depends on whether the company can win a final contract for a NASA program to launch a commercial space station that could replace the International Space Station. The program has a soft guarantee that NASA will buy time and space on any space station that goes into orbit. The contract is expected to be signed in mid-2026.

Without a NASA contract, the commercial viability of any space station is questionable, Haot said. “Winning this competition is a matter of survival.”