Author: Dmitriy Berenzon

Compiled by: Felix, PANews

When Satoshi Nakamoto published the Bitcoin white paper in 2009, his vision was to use a cryptographic network for payments, allowing it to flow freely on the Internet like information. Although the direction was correct, the technology, economic model, and ecosystem at the time were not suitable for commercializing use cases.

By 2025, the market has witnessed the convergence of several important innovations and developments that make this vision inevitable: stablecoins have been widely adopted by consumers and businesses, market makers and OTC desks can now easily hold stablecoins on their balance sheets, DeFi applications have created a strong on-chain financial infrastructure, there are a large number of deposit and withdrawal channels around the world, blockspace is faster and cheaper, embedded wallets simplify the user experience, and a clearer regulatory framework reduces uncertainty.

There is a great opportunity today to build a new generation of payment companies that leverage “Cryptorails” to achieve significantly better economics than the legacy system, which is encumbered by multiple rent-seeking intermediaries and antiquated infrastructure. These Cryptorails are becoming the backbone of a parallel financial system that operates in real time, 24/7, and is global in nature.

This article will:

- Explain the key components of the traditional financial system

- Overview of the main use cases for Cryptorails

- Discuss challenges that hinder continued adoption

- Share your predictions on the market outlook in five years

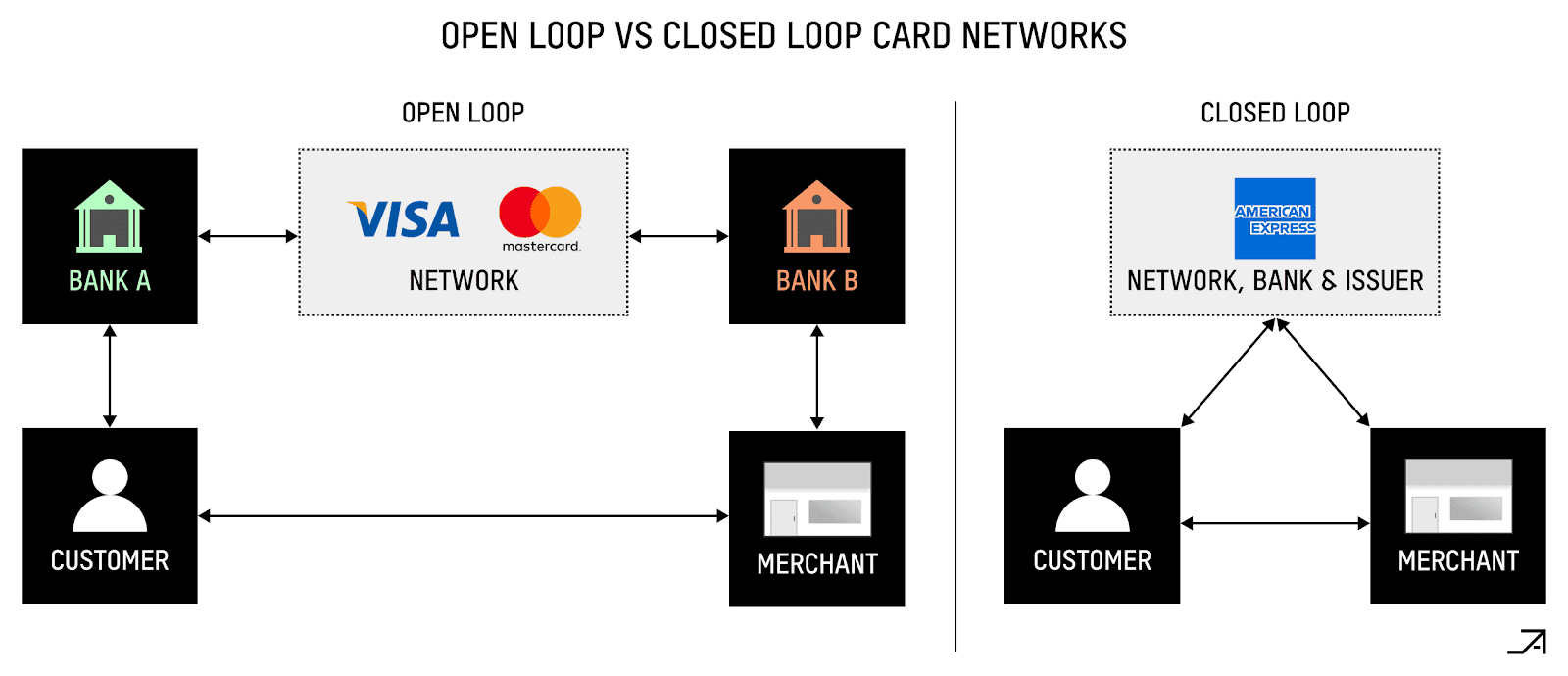

It’s worth noting that there are currently around 280 payment companies building on Cryptorails:

Source: Link

Existing channels

In order to understand the importance of Cryptorails, one must first understand the key concepts of existing payment rails and the complex market structure and system architecture within which they operate.

Card Networks

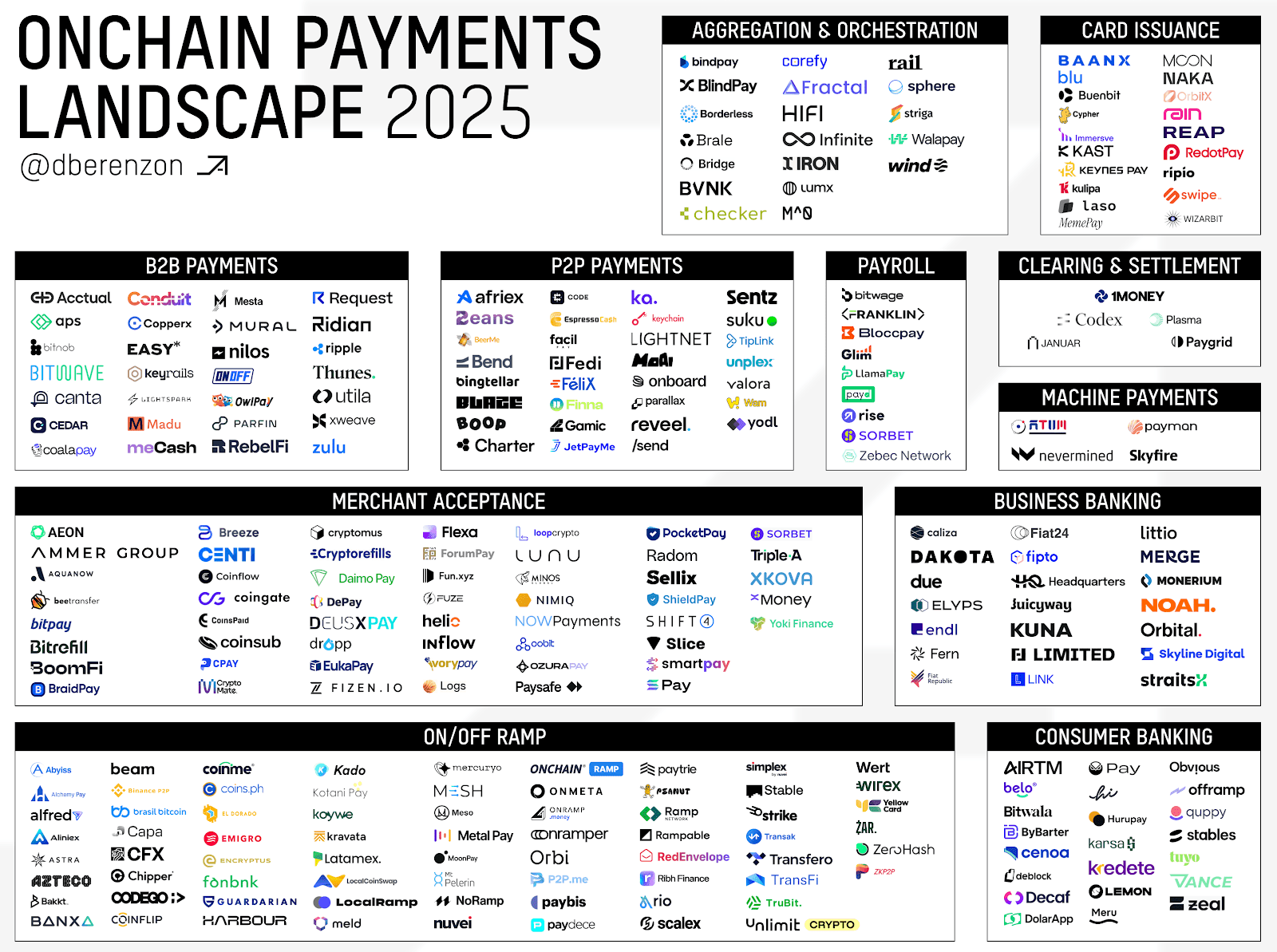

While the topology of card networks is complex, the key players in a transaction have remained the same for the past 70 years. Essentially, card payments involve four main players:

- Merchants

- cardholder

- Issuing Bank

- Acquiring Bank

The first two are easy, but the last two are worth explaining.

The issuing bank, or issuer, provides a credit or debit card to a customer and authorizes the transaction. When a transaction is requested, the issuing bank decides whether to approve it by checking the cardholder's account balance, available credit, and other factors. Credit cards essentially loan out the issuer's funds, while debit cards transfer money directly from the customer's account.

If merchants want to accept credit card payments, they need an acquirer (which can be a bank, processor, gateway, or independent sales organization) that is an authorized member of the card networks.

The card networks themselves provide the channels and rules for credit card payments. They connect acquirers with issuing banks, provide clearing functions, set participation rules and determine transaction fees. ISO 8583 remains the main international standard that defines how credit card payment information (such as authorization, settlement, refund) is structured and exchanged between network participants. In the network environment, issuers and acquirers are like their distributors - issuers are responsible for getting more cards into the hands of users, while acquirers are responsible for getting as many card terminals and payment gateways into the hands of merchants as possible so that they can accept card payments.

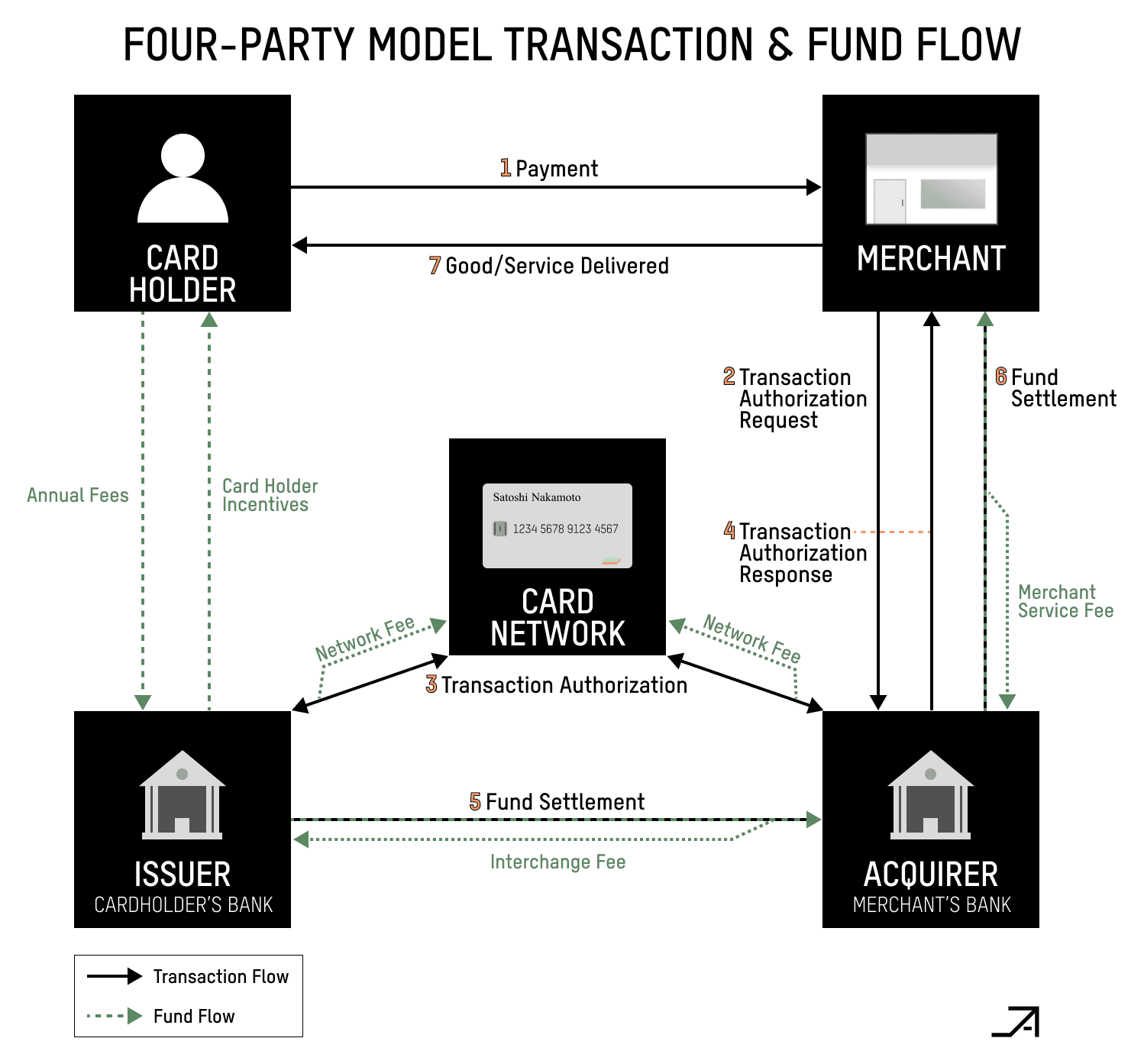

Furthermore, there are two types of card networks: “open loop” and “closed loop”. Open loop networks like Visa and Mastercard involve multiple parties: issuing banks, acquiring banks, and the card networks themselves. Card networks facilitate communications and transaction routing, but are more like a marketplace, relying on financial institutions to issue cards and manage customer accounts. Only banks are allowed to issue cards for open loop networks. Every debit or credit card has a Bank Identification Number (BIN) that is provided to banks by Visa, and non-bank entities like PayFacs require a “BIN sponsor” to issue cards or process transactions.

In contrast, closed-loop networks like American Express are self-sufficient, with one company handling all aspects of the transaction process—issuing its own cards, owning its own banks, and providing its own merchant acquiring services. Closed-loop systems offer more control and better margins, but at the expense of more limited merchant acceptance. In contrast, open-loop systems offer broader adoption, but at the expense of control and revenue sharing among participating parties.

Source: Arvy

The economics of payments are complex, with multiple layers of fees in the network. Interchange fees are part of the payment fees that issuing banks charge for providing access to their customers. While acquiring banks technically pay the interchange fees directly, the costs are often passed on to merchants. Card networks typically set interchange fees, which often make up the majority of the total cost of a payment. These fees vary widely across regions and transaction types. In the US, for example, consumer credit card fees range from ~1.2% to ~3%, while in the EU they are capped at 0.3%. There are also settlement fees, which are paid to the acquirer and are typically a percentage of the transaction settlement amount or volume.

While these are the most important players in the value chain, the reality is that today’s market structure is much more complex in practice:

Source: 22nd

While I won’t introduce all the participants one by one, there are a few important ones to point out:

Payment gateways encrypt and transmit payment information, connect with payment processors and acquirers for authorization, and communicate transaction approval or rejection to businesses in real time.

A payment processor processes payments on behalf of an acquiring bank. It forwards the transaction details from the gateway to the acquiring bank, which then communicates with the issuing bank through the card network to obtain authorization. The processor receives the authorization response and sends it back to the gateway to complete the transaction. It also handles settlement, which is the process by which the funds actually enter the merchant's bank account. Typically, a business sends a batch of authorized transactions to the processor, which submits it to the acquiring bank to initiate the transfer of funds from the issuing bank to the merchant's account.

A PayFac or Payment Service Provider (PSP) was pioneered by PayPal and Square around 2010 and acts like a mini payment processor that sits between merchants and acquiring banks. It effectively acts as an aggregator, bundling many smaller merchants into their system to achieve economies of scale and streamline operations by managing the flow of funds, processing transactions and ensuring payments. PayFacs hold the merchant IDs of the card networks and take on responsibilities such as compliance (e.g. AML laws) and underwriting on behalf of the merchants they work with.

An orchestration platform is a middleware technology layer that simplifies and optimizes the payment process for merchants. It connects to multiple processors, gateways, and acquirers through a single API, increasing transaction success rates, reducing costs, and improving performance by routing payments based on factors such as location or fees.

ACH

The Automated Clearing House (ACH) is one of the largest payment networks in the United States and is actually owned by the banks that use it. It was originally established in the 1970s, but really became popular when the US government began using it to send Social Security payments, which encouraged banks across the country to join the network. Today, it is widely used for payroll, bill payments, and B2B transactions.

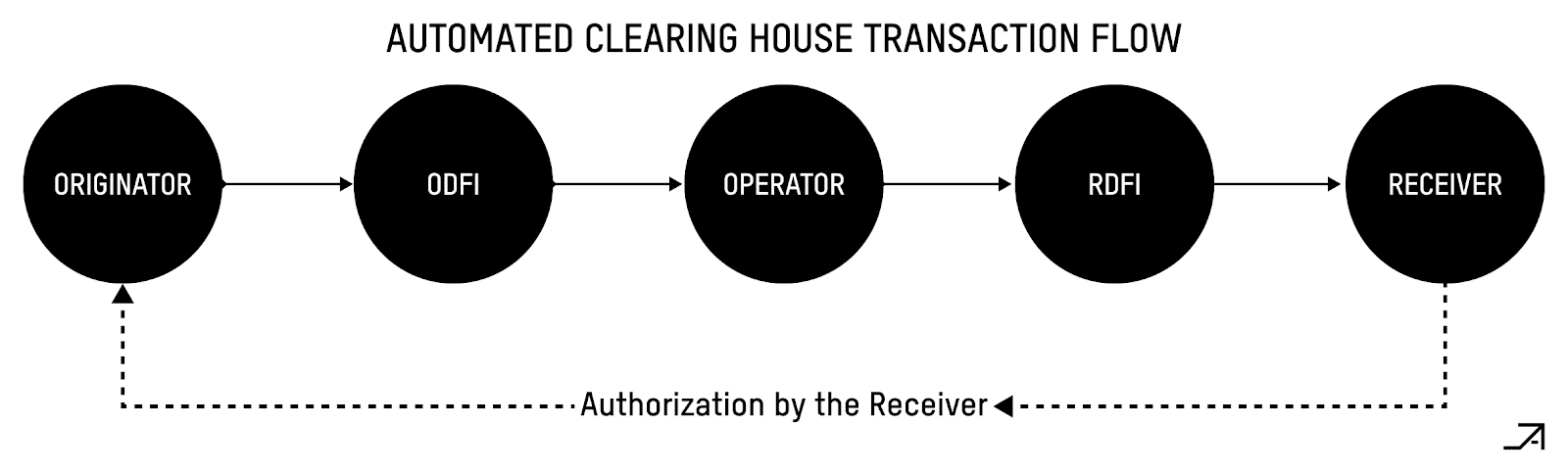

There are two main types of ACH transactions: “push” payments (you send money) and “pull” payments (someone takes money with your permission). When you get your paycheck via direct deposit or pay a bill online using your bank account, you’re using the ACH network. There are multiple players involved in the process: the company or person who initiates the payment (the originator), their bank (the ODFI), the receiving bank (the RDFI), and the operator who acts as the flow controller for all of these transactions. In the ACH process, the originator submits the transaction to the ODFI, which then sends it to the ACH operator, which then forwards it to the RDFI. At the end of each day, the operator calculates the net settlement total for its member banks (the Federal Reserve manages the actual settlement).

Source: America’s Payments System: A Guide for Payment Professionals

One of the most important things about ACH is how risk is handled. When a company initiates an ACH payment, its bank (ODFI) is responsible for making sure everything is legal. This is especially important for withdrawing payments—imagine if someone used your bank account information without permission. To prevent this, regulations allow disputes to be filed within 60 days of receiving a statement, and companies like PayPal have developed clever verification methods, such as making small test deposits to confirm account ownership.

The ACH system has been trying to keep up with modern demands. In 2015, they launched “Same-Day ACH”, which allows for faster processing of payments. Still, it relies on batch processing rather than real-time transfers, and has limitations. For example, you can’t send more than $25,000 in a single transaction, and it doesn’t work for international payments.

wire transfer

Wire transfers are the backbone of high-value payment processing, with two major systems in the United States: Fedwire and CHIPS. These systems process time-critical, guaranteed payments that require immediate settlement, such as securities transactions, major business transactions, and real estate purchases. Once executed, wire transfers are generally irrevocable and cannot be canceled or reversed without the consent of the recipient. Unlike conventional payment networks, which process transactions in batches, modern Wire systems use real-time gross settlement (RTGS), meaning that each transaction is settled individually as it occurs. This is an important feature because the system processes hundreds of billions of dollars every day, and the risk of banks using traditional net settlement failing within a day is too great.

Fedwire is an RTGS transfer system that allows participating financial institutions to send and receive same-day funds transfers. When a business initiates a wire transfer, its bank verifies the request, debits the funds from its account, and sends a message to Fedwire. The Federal Reserve Bank then immediately debits the funds from the remitting bank's account and deposits them into the receiving bank's account, which then deposits the funds to the ultimate recipient. The system operates weekdays from 9 p.m. to 7 p.m. Eastern Time the previous day and is closed on weekends and holidays.

Owned by large U.S. banks through clearing houses, CHIPS is smaller, serving only a handful of major banks. Unlike Fedwire’s RTGS approach, CHIPS is a net settlement engine, meaning the system allows for the aggregation of multiple payments between the same parties. For example, if Alice wants to send $10 million to Bob and Bob wants to send $2 million to Alice, CHIP will consolidate those payments into one $8 million payment from Alice to Bob. While this means CHIPS payments take longer than real-time transactions, most payments are still settled intraday.

Complementing these systems is SWIFT, which is not actually a payment system but a global messaging network for financial institutions. It is a member-owned cooperative whose shareholders represent more than 11,000 member organizations. SWIFT enables banks and securities firms around the world to exchange secure structured messages, many of which initiate payment transactions across various networks. According to Statrys, SWIFT transfers take about 18 hours to complete.

In the general process, the sender of funds instructs their bank to send a wire to the receiver. The value chain below is a simple case where two banks are part of the same wire transfer network.

Source: America’s Payments System: A Guide for Payment Professionals

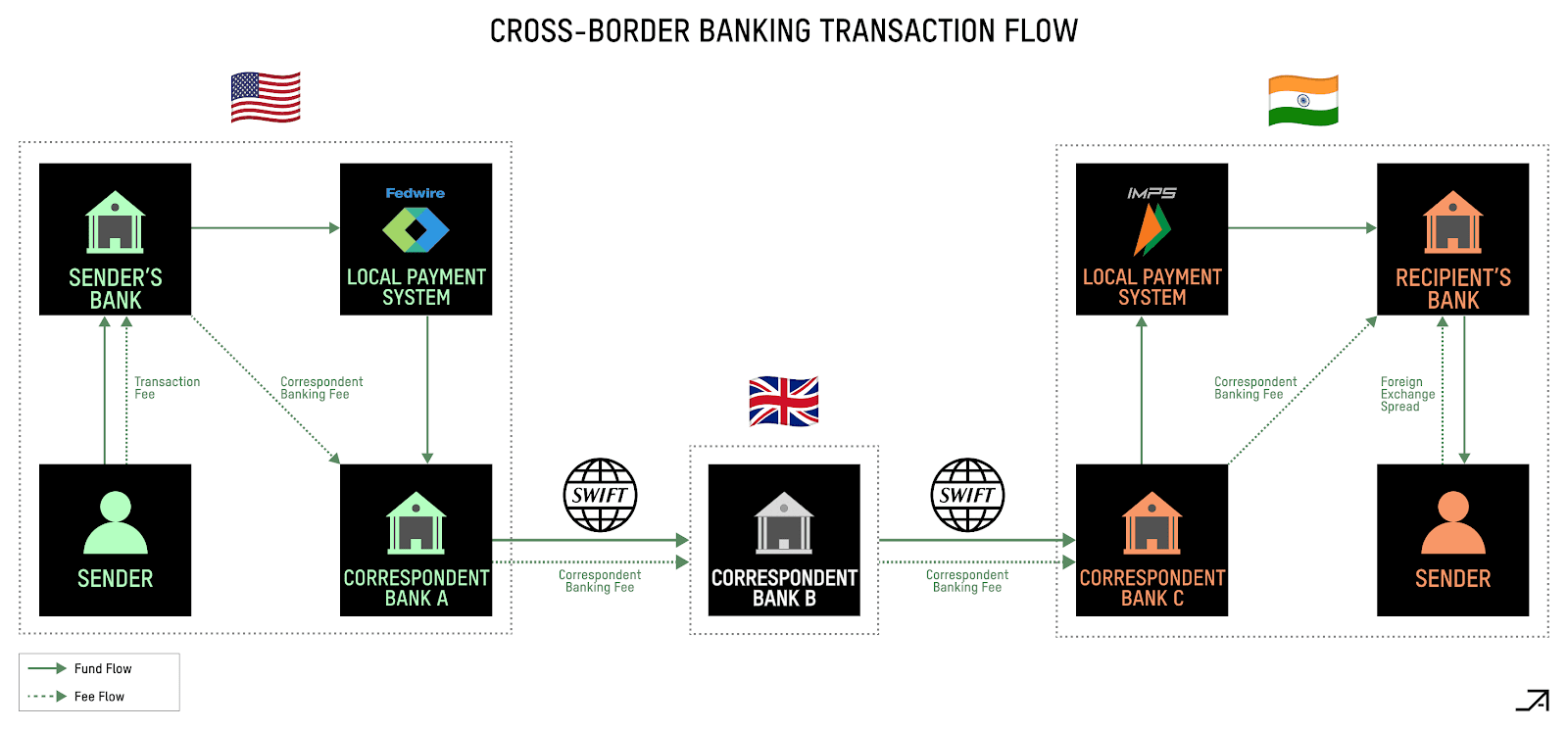

In more complex cases, particularly cross-border payments, transactions need to be executed through a correspondent banking relationship, often using SWIFT to coordinate payments.

Source: Matt Brown

Use Cases

Now that we have a basic understanding of traditional channels, we will explain the advantages of Cryptorails.

Cryptorails works best in situations where traditional dollar usage is limited but demand for the U.S. dollar is high. Think of places where people want dollars to store value but don’t have easy access to traditional dollar bank accounts. These are often countries with unstable economies, high inflation, currency controls, or underdeveloped banking systems, such as Argentina, Venezuela, Nigeria, Turkey, and Ukraine. In addition, the U.S. dollar is a superior store of value compared to most other currencies, and consumers and businesses often choose it because it can easily be used as a medium of exchange or converted into local fiat currency at the point of sale.

The advantages of Cryptorails are also most obvious in the scenario of globalized payments, because crypto networks know no borders. They rely on the existing Internet and provide global coverage. According to World Bank data, there are currently 92 RTGS (real-time gross settlement) systems in operation around the world, each of which is usually owned by its own central bank. While they are great for sending domestic payments in these countries, the problem is that they can't "talk to each other." Cryptorails can act as a glue between these different systems, and can also expand them to countries that don't have these systems.

Cryptorails are also most useful for payments that have some degree of urgency or generally have a high time preference. This includes cross-border supplier payments and foreign aid payments. They are also helpful in channels where the correspondent banking network is particularly inefficient. For example, despite geographic proximity, it is actually more difficult to send money from Mexico to the United States than from Hong Kong to the United States. Even from the United States to developed countries such as Europe, payments often go through four or more correspondent banks.

On the other hand, Cryptorails is less attractive for domestic transactions in developed countries, especially where card usage is high or real-time payment systems already exist. For example, intra-European payments flow smoothly through SEPA, while the stability of the euro eliminates the need for dollar-denominated alternatives.

Merchants adopt

Merchant adoption can be broken down into two distinct use cases: front-end integration and back-end integration. On the front-end, merchants can directly accept cryptocurrencies as a payment method for their customers. While one of the oldest use cases, historically there hasn’t been a lot of volume because few people held crypto, even fewer wanted to spend it, and for those who did, there were limited useful options. Today the market is different, as more people hold crypto assets, including stablecoins, and more merchants are accepting them as a payment option because it allows them to reach new customer segments and ultimately sell more goods and services.

From a geographic perspective, the majority of volume comes from businesses selling to consumers in early cryptocurrency adopter countries, which are typically emerging markets like Vietnam and India. From a merchant perspective, the majority of demand comes from online gambling and retail stock brokerages looking to reach users in emerging markets, Web2 and Web3 markets like watch vendors and content creators, and gaming like fantasy sports and sweepstakes.

The "front end" merchant acceptance process typically looks like this:

- PSP usually creates a wallet for the merchant after KYC/KYB

- User sends cryptocurrency to PSP (Payment Service Provider)

- The PSP converts cryptocurrencies into fiat currency through a liquidity provider or stablecoin issuer and sends the funds to the merchant’s local bank account, possibly using other authorized partners

What is preventing this use case from continuing to gain adoption is primarily a psychological challenge, as cryptocurrencies do not seem “real” to many people. There are two main user personas that need to be addressed: one that has absolutely no regard for its value and wants to keep everything as magical internet money, and one that is pragmatic and would just deposit its funds directly into a bank.

Additionally, consumer adoption of cryptocurrencies in the United States is more difficult because credit cards actually pay consumers 1-5% cash back on purchases. Attempts to convince merchants to promote cryptocurrency payments directly to consumers as an alternative to credit cards have so far been unsuccessful. Merchant Customer Exchange was launched in 2012 and failed in 2016 due to its inability to start the consumer-side adoption flywheel. In other words, it is difficult for merchants to directly incentivize users to switch from using card payments to using crypto assets because payments are already "free" for consumers, so the value proposition should be solved at the consumer level first.

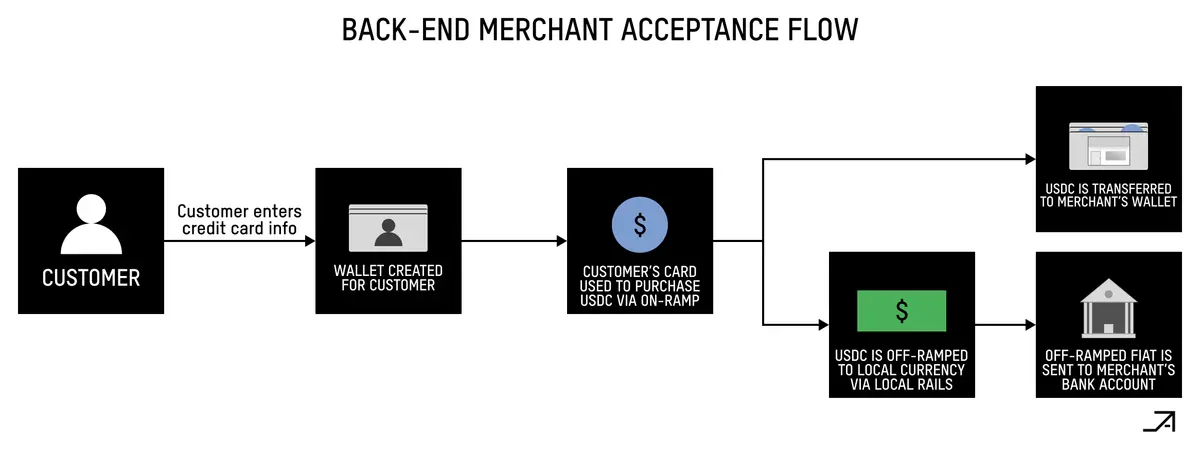

On the backend, Cryptorails provides merchants with faster settlement times and access to funds. Settlements can take 2-3 days for Visa and Mastercard, 5 days for American Express, and even longer for international settlements, such as around 30 days in Brazil. In some use cases, such as marketplaces like Uber, merchants may need to pre-fund their bank accounts to receive payments before settlement. Instead, people can effectively deposit funds through credit cards, transfer funds on-chain, and transfer them directly to the merchant’s bank account in local currency. Not only does this flow improve working capital because less money is tied up in the transfer process, merchants can also further improve fund management by freely and instantly exchanging between digital dollars and yield assets such as tokenized U.S. Treasuries.

Specifically, the "backend" merchant acceptance process might look like this:

- Customer enters card information to complete transaction

- The PSP creates a wallet for the customer, and the user funds the wallet using an on-ramp that accepts traditional payment methods

- Credit card transaction buys USDC, which is then sent from the customer’s wallet to the merchant’s wallet

- PSP can choose to transfer to the merchant’s bank account through native channels T+0 (i.e. same day)

- PSP usually receives funds from acquiring banks within T+1 or T+2 (i.e. within 1-2 days)

Debit Card

The ability to link a debit card directly to a non-custodial smart contract wallet creates a powerful bridge between blockchain space and the real world, driving organic adoption across different user personas. In emerging markets, these cards are becoming a primary spending tool, increasingly replacing traditional banks. Interestingly, even in countries with stable currencies, consumers are leveraging these cards to gradually accumulate USD savings while avoiding foreign exchange fees on purchases. High net worth individuals are also increasingly using these cryptocurrency-pegged debit cards as an efficient tool to spend USDC globally.

Debit cards are more attractive than credit cards for two reasons: they face fewer regulatory restrictions (e.g., MCC 6051 is outright rejected in Pakistan and Bangladesh, where capital controls are strict), and they carry a lower risk of fraud, as chargebacks of settled crypto transactions raise serious liability issues for credit cards.

In the long run, cards tied to crypto wallets for mobile payments may actually be the best way to combat fraud, since there is biometric verification on the phone: scan your face, spend, top up money from your bank account to your wallet.

money transfer

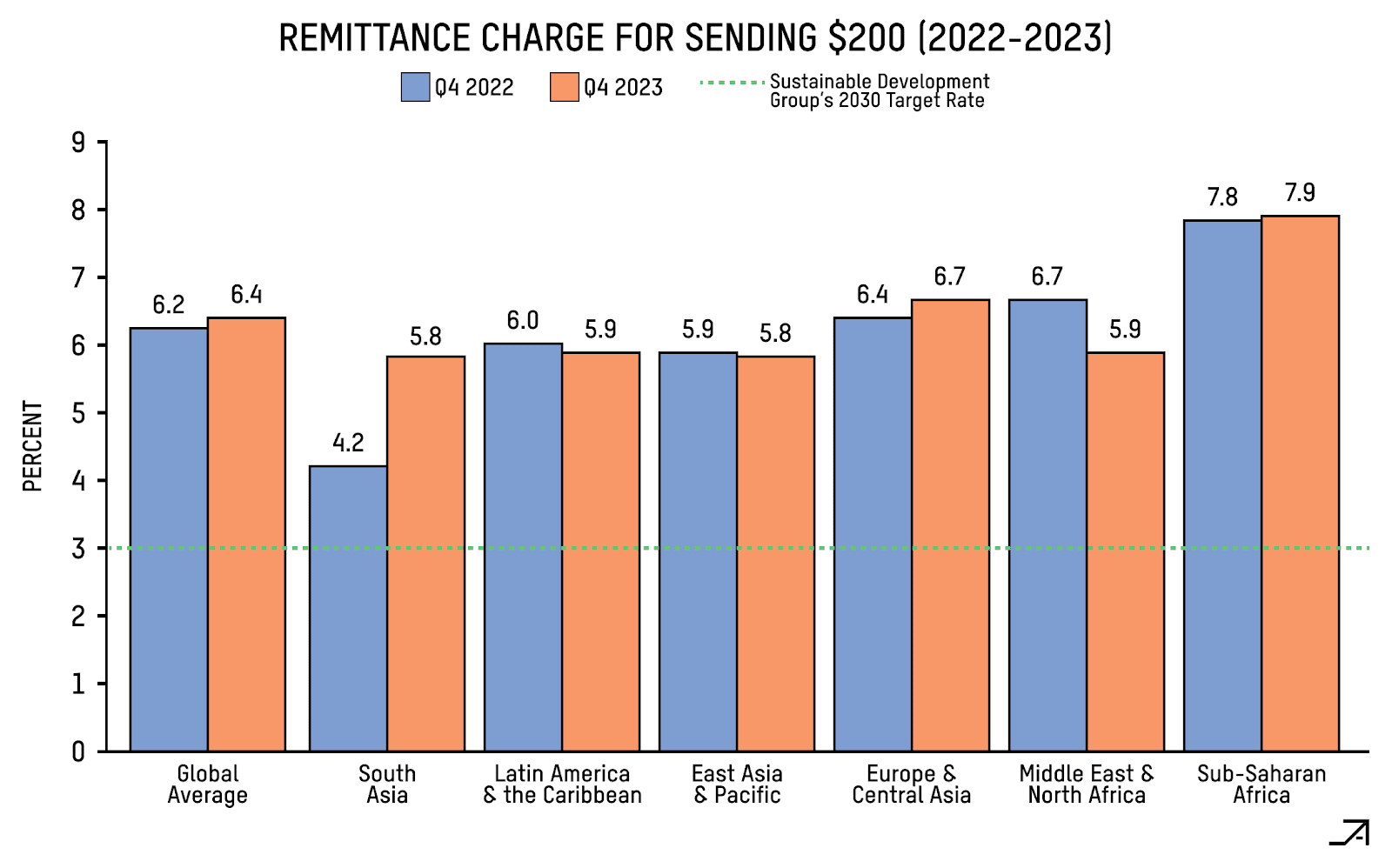

Remittances are the transfer of funds from the country of work to the home country by people who have emigrated to find work and want to send money back home. According to the World Bank, remittances will total about $656 billion in 2023, equivalent to the GDP of Belgium.

Traditional remittance systems are costly. On average, cross-border remittances cost 6.4% of the amount transferred, but these fees can vary widely—transfers from Malaysia to India cost 2.2% (and even less for high-volume corridors like the U.S. to India). Banks tend to have the highest fees, around 12%, while money transfer operators (MTOs) like MoneyGram charge an average of 5.5%.

Source: World Bank

Cryptorails offers a faster and cheaper way to send money. The growth of companies using Cryptorails is largely dependent on the size of the broader remittance market, with the largest volumes being from the US to Latin America (particularly Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil), the US to India, and the US to the Philippines. A big driver of this growth is non-custodial embedded wallets like Privy that provide users with a Web2-grade user experience.

The process of sending money using Cryptorails might look like this:

- The sender enters the PSP via a bank account, debit card, credit card, or directly to an on-chain address; if the sender does not have a wallet, one is created for them

- PSP converts USDT/USDC into the recipient’s local currency, either directly or using a market maker or OTC partner.

- The PSP pays the fiat currency directly to the recipient’s bank account, or through a local payment gateway; alternatively, the PSP can first generate a non-custodial wallet for the recipient to claim the funds, giving them the option to keep them on-chain.

- In many cases, the recipient needs to complete KYC before receiving the funds

That being said, the road to launch for crypto remittance projects is still difficult. One issue is that people often need to be incentivized to transfer from MTOs (remittance operators), which can be expensive. Another issue is that transfers on most Web2 payment applications are already free, so local transfers alone are not enough to overcome the network effects of existing applications. Finally, while the on-chain transfer component works well, it still needs to interact with TradFi (traditional finance) at the "edge", so it may end up with the same or even worse problems due to costs and friction. In particular, payment gateways that convert to local fiat currency and pay through methods such as mobile phones or self-service terminals will account for the largest profits.

B2B Payments

Cross-border (XB) B2B payments are one of the most promising applications for Cryptorails. Payments through the correspondent banking system can take weeks to settle, and in some extreme cases even longer - one founder said it took them 2.5 months to send supplier payments from Africa to Asia. As another example, cross-border payments from Ghana to Nigeria (two bordering countries) can take weeks and cost up to 10% in transfer fees.

Additionally, cross-border settlements are slow and expensive for PSPs. For companies like Stripe that process payments, it can take up to a week to pay international merchants, and they have to lock up capital to cover fraud and chargeback risks. Shortening the conversion cycle will free up a lot of working capital.

Cryptorails has gained significant traction with B2B XB payments, primarily because merchants care more about fees than consumers. Reducing transaction costs by 0.5-1% doesn’t sound like much, but it adds up when volumes are high, especially for businesses operating on thin margins. In addition, speed matters. Getting payments done in hours instead of days or weeks has a significant impact on a company’s working capital. Additionally, businesses are more tolerant of poorer user experiences and more complex experiences than consumers who expect a smooth experience.

Meanwhile, the cross-border payments market is massive — estimates vary widely from source to source, but according to McKinsey, revenues are around $240 billion and volumes are around $150 trillion in 2022. That said, building a sustainable business is still difficult. While a “stablecoin sandwich” — exchanging local currency for stablecoins and back again — is certainly faster, it’s also expensive because converting foreign exchange on both sides eats into profits. While some companies have tried to address this by building in-house market-making arms, it’s very expensive and difficult to scale. In addition, customers are also concerned about regulation and risk, and a lot of education is needed. That said, FX costs could fall rapidly over the next two years as stablecoin legislation opens the door for more businesses to hold and use digital dollars. As more on-ramps and token issuers will have direct banking relationships, they will be able to effectively offer wholesale FX rates at internet scale.

XB Supplier Payments

For B2B payments, most cross-border transactions revolve around import payments to suppliers, typically with buyers in the US, Latin America, or Europe and suppliers in Africa or Asia. These channels are particularly troublesome because local channels in these countries are underdeveloped and difficult for companies to enter because they cannot find local banking partners. Cryptorails can also help alleviate pain points in specific countries. In Brazil, for example, you cannot pay millions of dollars using traditional channels, which makes it difficult for businesses to make international payments. Some well-known companies, such as SpaceX, are already using Cryptorails for this use case.

XB Accounts Receivable

Businesses with customers around the world often have difficulty collecting funds in a timely and efficient manner. They often work with multiple PSPs to collect funds for them locally, but need a way to receive funds quickly, which can take days or even weeks, depending on the country. Cryptorails is faster than SWIFT transfers and can compress the time to T+0.

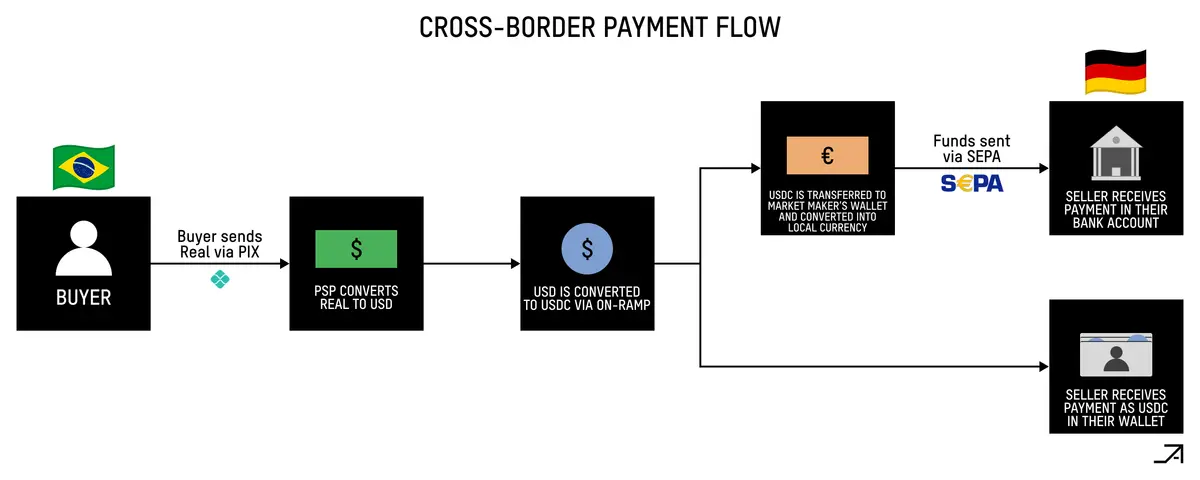

Here is an example payment flow for a Brazilian business purchasing goods from a German business:

- The buyer sends the Real to the PSP via PIX

- PSP converts Real to USD and then to USDC

- PSP sends USDC to the seller’s wallet

- If the seller wants local fiat currency, the PSP will send USDC to a market maker or trading desk to convert to local currency

- If the seller has a license/bank account, the PSP can remit the money to the seller through local channels, if not, a local partner can be used

Financial Operations

Companies can also use Cryptorails to improve financial operations and accelerate global expansion. They can hold USD and use local deposits and withdrawals to reduce foreign exchange risk and enter new markets faster, even if local banking providers support them. They can also use Cryptorails to reorganize and repatriate funds between countries in which they operate.

Foreign Aid Payments

Another common use case for B2B is time-critical payments, where these Cryptorails can be used to get to the recipient faster. One example is foreign aid payments - allowing NGOs to use Cryptorails to send money to local export agents, who can then individually make payments to eligible individuals. This works especially well in economies with very poor local financial systems and/or governments. For example, in a country like South Sudan, where the central bank is collapsing, local payments can take over a month. But as long as there is a mobile phone and an internet connection, there are ways to bring digital currency into the country, and individuals can exchange digital currency for fiat currency and vice versa.

The payment flow for this use case might be as follows:

- NGOs send funds to PSP

- PSP sends bank transfer to OTC partner

- OTC partners convert fiat currency into USDC and send it to local partners’ wallets

- Local partners transfer USDC through peer-to-peer (P2P) traders

Payroll

From a consumer perspective, one of the most promising early adopters is freelancers and contractors, especially in emerging markets. The value proposition for these users is that more money ends up in their pockets, rather than going to intermediaries, and that money can be digital dollars. This use case also brings cost benefits to businesses sending large-scale payments to another party, and is particularly useful for crypto-native companies (such as exchanges) that already hold most of their funds in cryptocurrency.

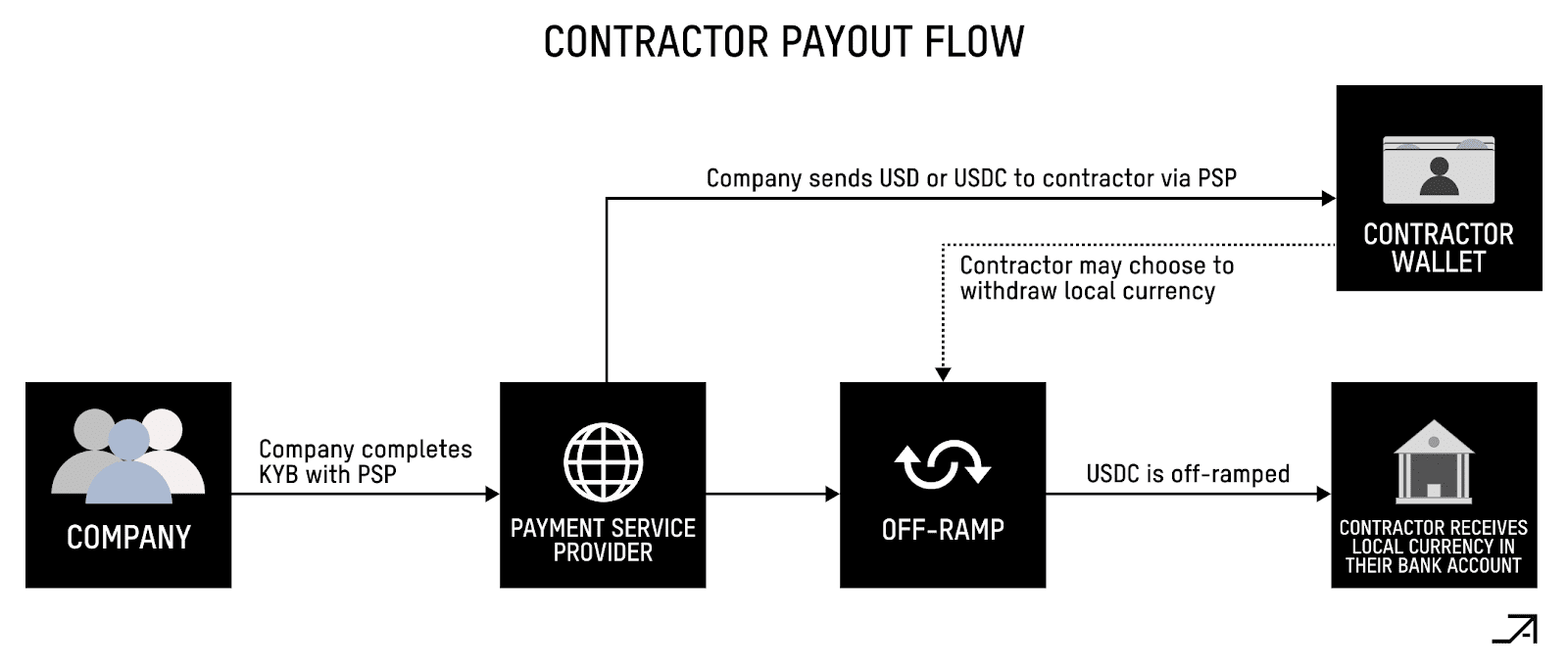

The payment process for contractor payments is usually as follows:

- Companies conduct KYB/KYC with PSP

- The company sends USD to the PSP or USDC to the wallet address associated with the contractor

- The contractor can decide whether to keep it as cryptocurrency or withdraw it to a bank account, and the PSP usually enters into some master service agreements with one or more off-site partners who hold the relevant licenses in their respective jurisdictions to make local payments.

Deposit and Withdrawal

Funding is a crowded market. While many early attempts failed to scale, the market has matured over the past few years with many companies operating sustainably and providing local payment channels around the world. While funding can be used as a standalone product (such as simply buying crypto assets), it is arguably the most critical part of the payment process when bundling services such as payments.

There are usually three components to establishing on-ramps and off-ramps: obtaining the necessary licenses (e.g. VASP, MTL, MSB), securing local banking partners or PSPs to access local payment channels, and connecting with market makers or OTC desks for liquidity.

Deposits were initially dominated by exchanges, but now more and more liquidity providers (from smaller FX and OTC desks to large trading firms such as Cumberland and FalconX) are offering deposit channels. These firms can typically handle up to $100 million in volume per day and are less likely to exhaust liquidity on popular assets. Some teams may even prefer these channels because they can promise spreads.

Non-US outbound channels are often much more difficult than US inbound channels due to licensing, liquidity, and orchestration complexities. This is especially true in Latin America and Africa, where there are dozens of currencies and payment methods. For example, you can use PDAX in the Philippines because it is the largest cryptocurrency exchange there, but in Kenya you need to use multiple local partners such as Clixpesa, Fronbank, and Pritium depending on the payment method.

P2P channels rely on a network of “agents” — local individuals, mobile money providers, and small businesses like supermarkets and pharmacies — who provide fiat and stablecoin liquidity. These agents are particularly prevalent in Africa, where many already operate mobile money stalls for services like MPesa, and their primary motivation is financial incentives — making money through transaction fees and foreign exchange spreads. In fact, for individuals in high-inflation economies like Venezuela and Nigeria, being an agent can be more lucrative than traditional service jobs like taxi driving or delivering food. They can also work from home using their phones, and typically only need a bank account and mobile money to get started. What makes the system particularly powerful is its ability to support dozens of local payment methods without any formal licensing or integration, as transfers occur between individual bank accounts.

It is worth noting that the foreign exchange rates of P2P channels are generally more competitive. For example, the Bank of Khartoum in Sudan often charges up to 25% in foreign exchange fees, while the local crypto P2P channels offer foreign exchange fees of 8-9%, which is actually the market interest rate rather than the bank-imposed interest rate. Similarly, P2P deposit channels are able to provide foreign exchange rates that are about 7% lower than the bank exchange rates in Ghana and Venezuela. Generally speaking, the interest rate spread is smaller in countries with a larger supply of US dollars. In addition, the best markets for P2P deposits are those with high inflation, high smartphone penetration, weak property rights, and unclear regulatory guidelines, because financial institutions will not touch cryptocurrencies, which creates an environment for self-custody and P2P to flourish.

The payment flow for a P2P deposit may look like this:

- Users can select or automatically designate a counterparty or “agent” that already has USDT, which is usually held in custody by a P2P platform.

- Users send fiat currency to agents via local channels

- The agent confirms receipt and sends USDT to the user

From a market structure perspective, most access points are commoditized, and customer loyalty is low as they will typically choose the cheapest option. To remain competitive, local channels may need to expand coverage, optimize for the most popular channels, and find the best local partners. In the long term, we may see consolidation into a few access points per country, each with a comprehensive license, supporting all local payment methods, and providing the greatest liquidity. Aggregators will be particularly useful in the medium term as local providers are often faster and cheaper, and combined options often offer consumers the best pricing and completion rates.

The good news from a consumer perspective is that fees are likely to go to zero. We’ve seen this today on Coinbase, where an instant transfer from USD to USDC costs $0. In the long term, most stablecoin issuers are likely to offer this service to large wallets and fintech companies, further compressing fees.

license

Licensing is a painful but necessary step to scaling Cryptorails adoption. For startups, there are two approaches: partner with an already licensed entity or obtain a license independently. Partnering with a licensed partner allows startups to bypass the significant costs and lengthy time required to obtain a license on their own, but with lower profit margins since the majority of revenue goes to the licensed partner. Alternatively, startups can choose to invest upfront (potentially hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars) to obtain a license independently. While this path often takes months or even years (one project said it took them 2 years), it enables startups to deliver a more comprehensive product directly to users.

While there are established strategies for obtaining licenses in many jurisdictions, achieving global licensing coverage is extremely challenging or even impossible because each region has its own unique money transmission regulations and you need more than 100 licenses to achieve global coverage. For example, in the United States alone, a project needs to obtain a money transmitter license (MTL) in each state, a BitLicense in New York, and a money service business (MSB) registration with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. It costs between $500,000 and $2 million to obtain the MTL for all states alone and can take up to a year.

challenge

Payment adoption is often difficult because they are a chicken and egg problem. You either get consumers to widely adopt a payment method, forcing merchants to accept it, or you get merchants to use a specific payment method, forcing consumers to adopt. For example, credit cards were a niche market in Latin America until Uber became popular in 2012; everyone wanted a credit card because it allowed them to use Uber, which was safer and (initially) cheaper than taxis. This allowed other on-demand apps like Rappi to become popular because now people had smartphones and credit cards. This created a virtuous cycle where more and more people wanted a credit card because there were more cool apps that required credit cards to pay.

This also applies to mainstream consumer adoption of Cryptorails. I don’t see a use case where using stablecoins for payments is particularly beneficial or outright necessary, though debit cards and remittance apps are closer. P2P apps have a chance there too if they can unlock entirely new online behaviors — micropayments and creator payments seem like exciting candidates. This is largely true of general consumer apps as well, which won’t be adopted without a step-change improvement to the status quo.

There are still some problems with deposits and withdrawals:

- High failure rate: If you have ever tried to deposit using a credit card, you will understand

- User experience friction: While early adopters may accept the pain of onboarding assets through exchanges, the early majority will likely use them directly in specific apps. To support this, smooth in-app onboarding is required, preferably through Apple Pay

- High costs: Access is still very expensive - fees can still be as high as 5-10% depending on the provider and region

- Varying quality: Reliability and compliance still vary too much, especially for non-USD currencies

One issue that is not discussed in depth is privacy. While privacy is not a serious issue for individuals or companies today, it will become an issue once Cryptorails is adopted as the primary mechanism for commerce. When malicious actors begin to monitor the payment activity of individuals, companies, and governments through public keys, there will be serious negative consequences. One way to address this in the short term is to "protect privacy through obscurity" by starting a new wallet every time you need to send or receive funds on-chain.

Additionally, building a banking relationship is often the hardest part, as it’s another chicken-and-egg problem. If a banking partner gets volume and makes money, they’ll take you on, but you need a bank to get that volume in the first place. Additionally, there are only 4-6 small US banks that currently support crypto payment companies, and several of those banks have reached their limits with internal compliance. This is partly because crypto payments today are still classified as a “high-risk activity” similar to marijuana and online gambling.

The reason for this is that compliance is still not as good as it is with traditional payment companies. This includes AML/KYC and Travel Rule compliance, OFAC screening, cybersecurity policies, and consumer protection policies. Even more challenging is building compliance directly into Cryptorails, rather than relying on outside solutions and companies.

Outlook

On the consumer side, we are at a stage where certain segments of the population are beginning to accept stablecoins, especially freelancers, contractors, and remote workers. We are also getting closer to the demand for dollars in emerging economies by onboarding card networks and providing consumers with USD exposure and daily spending power. In other words, debit cards and embedded wallets have become the "bridge" to bring cryptocurrencies off-chain in a form that is intuitive to mainstream consumers. On the business side, we are at the beginning stages of mainstream adoption. Companies are using stablecoins on a large scale and will increase significantly over the next decade.

With that in mind, here are 20 predictions for where the industry might be in five years:

- Between $200 billion and $500 billion is paid through Cryptorails annually, driven primarily by B2B payments.

- More than 30 new banks launched on Cryptorails worldwide

- Dozens of crypto firms acquired as fintechs race to stay relevant

- Some crypto companies (likely stablecoin issuers) will acquire distressed fintechs and banks that are struggling due to high CAC and operating costs

- There are about 3 crypto networks (L1 and L2) emerging and scaling, with architectures designed for payments. Such networks are similar to Ripple in spirit, but will have a reasonable technology stack, economic model, and go-to-market approach.

- 80% of online merchants will accept cryptocurrencies as a means of payment, either through existing PSPs to expand their offerings or by providing them with a better experience through crypto-native payment processors

- The card network will expand to cover approximately 240 countries and territories (currently approximately 210), using stablecoins as a last-mile solution

- The majority of transaction volume for more than 15 remittance corridors around the world will be conducted through Cryptorails

- On-chain privacy will eventually be adopted, driven by businesses and countries using Cryptorails, not consumers

- 10% of all foreign aid spending will be sent via Cryptorails

- The deposit and withdrawal market structure will solidify, with 2-3 providers per country capturing the majority of volume and partnerships

- The number of P2P deposit and withdrawal liquidity providers will become as numerous as the number of food delivery workers. As trading volumes increase, agents will become a financially sustainable job and continue to be at least 5-10% cheaper than the FX rates quoted by banks.

- Over 10 million remote workers, freelancers, and contractors will be paid for their services through Cryptorails (directly in stablecoins or local currencies)

- 99% of AI agent commerce (including agent-to-agent, agent-to-person, and person-to-agent) will be conducted on-chain via Cryptorails

- More than 25 well-known US partner banks will provide support for companies running on Cryptorails

- Financial institutions will try to issue their own stablecoins to facilitate global real-time settlement

- Standalone “crypto Venmo” apps have yet to catch on because the user roles are still too niche, but large messaging platforms like Telegram will integrate Cryptorails and start using it for P2P payments and remittances

- Loan and credit companies will start receiving and disbursing payments through Cryptorails to improve their working capital as less funds are tied up in the transfer process

- Some non-USD stablecoins will begin to be tokenized on a large scale, giving rise to an on-chain foreign exchange market

- Due to government bureaucracy, CBDCs are still in the experimental stage and have not yet reached commercial scale

in conclusion

As Patrick Collison suggests, Cryptorails are the superconductors of payments, they form the basis of a parallel financial system that offers faster settlement times, lower fees, and the ability to operate seamlessly across borders. It took a decade for the idea to mature, but today sees hundreds of companies working to make it a reality. The next decade will see Cryptorails at the heart of financial innovation, driving global economic growth.

Related reading: 20,000-word research report on crypto payments: From electronic cash, tokenized currency, to the future of PayFi