Author: shu fen

The dilemma of U.S. debt cannot be solved in a short period of time, and in the end it still has to be handled according to the two paths of the debt crisis mentioned above.

This article refers to Dalio’s new book “How Nations Go Bankrupt”, and at the end combines my personal views to sort out the opportunities and risks of the US debt cycle, which is only used as an aid to investment decisions.

Let me first introduce Dalio, the founder of Bridgewater Associates. He has successfully predicted major economic events such as the 2008 financial crisis, the European debt crisis, and Brexit many times. He is known as the Steve Jobs of the investment world. Now let’s get to the main text.

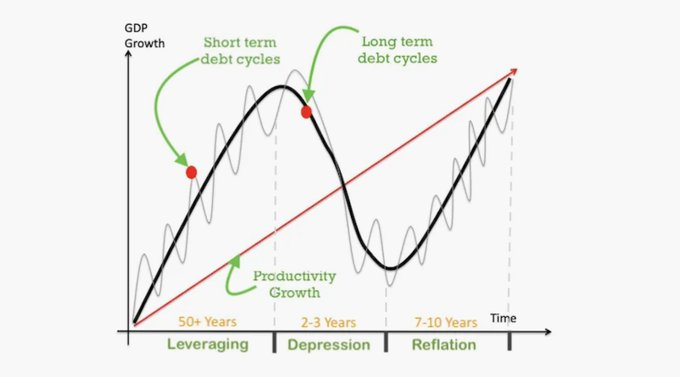

In the past, when studying debt, we usually refer to the credit cycle (about 6 years ± 3 years) that is synchronized with the business cycle, while the big debt cycle is more important and more fundamental. This is because since 1700, there have been about 750 currencies or debt markets in the world, but only about 20% of them still exist today. Even the currencies that survived have mostly experienced severe depreciation, which is closely related to the "big debt cycle" in the book.

The core difference between a small debt cycle and a large debt cycle is whether the central bank has the ability to reverse the debt cycle. In the traditional deleveraging process of a small debt cycle, the central bank will lower interest rates and increase credit supply. But for a large debt cycle, the situation will be very tricky because debt growth is no longer sustainable. A typical path to deal with a large debt cycle is: private sector health -> private sector over-borrowing and difficulty in repaying -> government departments provide help, over-borrowing -> central bank printing money and purchasing government debt to provide help (central bank is the last borrower).

The Great Debt Cycle typically lasts about 80 years and is divided into five phases:

1) Sound Money Stage: Initially, interest rates are very low, and the returns from borrowing are higher than the cost of capital, so debt expansion occurs.

2) Debt Bubble Stage: As debt expands and the economy begins to prosper, prices of certain assets (stocks, real estate, etc.) begin to rise. As asset prices rise and the economy continues to prosper, the private sector becomes more confident in its ability to repay debts and its rate of return on assets, and thus continues to expand debt.

3) Bubble burst stage (Top Stage): Asset prices have reached the bubble stage, but debt expansion has not stopped.

4) Deleveraging Stage: A wave of debt defaults breaks out, asset prices plummet, total demand shrinks, and the economy falls into a debt-deflation cycle (Fisher effect). Nominal interest rates fall to the zero lower bound, real interest rates rise due to deflation, and debt repayment pressure intensifies.

5) Debt Crisis Stage: As the asset bubble bursts, the debt bubble bursts at the same time. In this case, people who borrow money to buy assets may not be able to repay their debts. At this time, the entire economy faces bankruptcy and debt restructuring. This stage also marks the end of the big debt crisis, the achievement of a new balance, and the beginning of a new cycle.

In each of these five stages, the central bank must adopt different monetary policies to ensure the stability of debt and the economy, so we can also observe the current stage of the debt cycle through monetary policy.

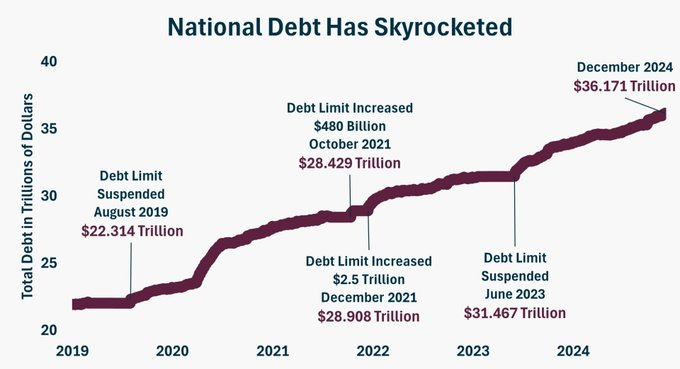

Currently, the United States has experienced 12.5 short-term debt cycles since 1945, and the United States' debt interest expenditure this year is expected to exceed $1 trillion, while the total government revenue is only $5 trillion. In other words, for every $4 the US government collects, it has to pay $1 to pay debt interest!

If this trend continues, it will become increasingly difficult for the U.S. government to repay its debts and will eventually be forced to monetize its debts (print money to repay debts), which will further push up inflation and cause serious currency depreciation. Therefore, the United States is currently in the second half of the big debt cycle, on the verge of Stage 3, the "bubble burst stage", which means that a debt crisis may be imminent.

Below we review the first long debt cycle that the United States experienced from 1981 to 2000, which is divided into several short cycles.

The first short cycle (1981-1989): The second oil crisis in 1979 brought the United States into the era of "stagflation 2.0". From February to April 1980, the prime lending rate of US banks was raised nine times from 15.25% to 20.0%. The inflation rate was at a historical high, and the interest rate was also at a historical high. In order to avoid systemic risks, monetary policy turned from tight to loose. From May to July 1980, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates three times, 100 BP each time, and the interest rate was lowered from 13.0% to 10.0%, a total of 300 BP. After Reagan took office in 1981, he significantly increased defense spending. The government leverage ratio surged during this period, and the stock of debt expanded rapidly during this period, reaching the highest point of the long debt cycle in 1984, with the deficit accounting for as high as 5.7%. In May, Continental Illinois Bank, one of the top ten banks in the United States, suffered a "run". On the 17th of the same month, the bank accepted temporary financial assistance from the FDIC, which was the most significant bank bankruptcy resolution in the history of the FDIC. In June, the bank's prime lending rate continued to rise until the Plaza Accord in 1985, which forced the dollar to depreciate. After the Plaza Accord was signed, the Gramm-Ludman-Hollings Act of 1985 was introduced, requiring the federal government to basically achieve a balanced fiscal budget by 1991. On October 28, 1985, Federal Reserve Chairman Volcker delivered a speech, saying that the economy needed the help of lower interest rates. During this period, the Federal Reserve gradually lowered the interest rate from 11.64% to 5.85% to re-stimulate the economy.

However, Greenspan, who took office as the chairman of the Federal Reserve in 1987, tightened monetary policy again. The rising financing costs led to a decrease in the willingness of enterprises and residents to finance. The interest rate hike also became an important reason for the "Black Monday" stock market crash, and the economic growth rate further declined. In 1987, Reagan signed the bill to reduce the fiscal deficit, and the increase in government leverage began to decline. The increase in leverage ratios of various departments continued to slow down until the end of 1989, and the scale of social leverage entered a sideways stage.

The second short cycle (1989-1992): The Gulf War broke out in August 1990, international oil prices rose sharply, CPI rose to the highest point since 1983, GDP growth reached negative growth in 1991, and unemployment continued to rise sharply in March 1991. In order to reverse the dilemma of economic stagflation, the Federal Reserve adopted an accommodative monetary policy during this period, and lowered the federal funds target rate from the cycle high of 9.8125% to 3%. The large amount of fiscal expenditure caused by launching the war also caused a surge in the leverage ratio of government departments, which triggered an increase in the incremental social leverage ratio in 1991. On April 1, 1992, a stock market crash occurred in Japan, and the Nikkei index fell below 17,000 points. At this time, it had fallen 56% from the historical high of 38,957 points in early 1990; the stock markets of Japan, Britain, France, Germany, and Mexico all experienced a chain decline due to economic deterioration. In response to the global economic recession, on July 2, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates again by 50BP.

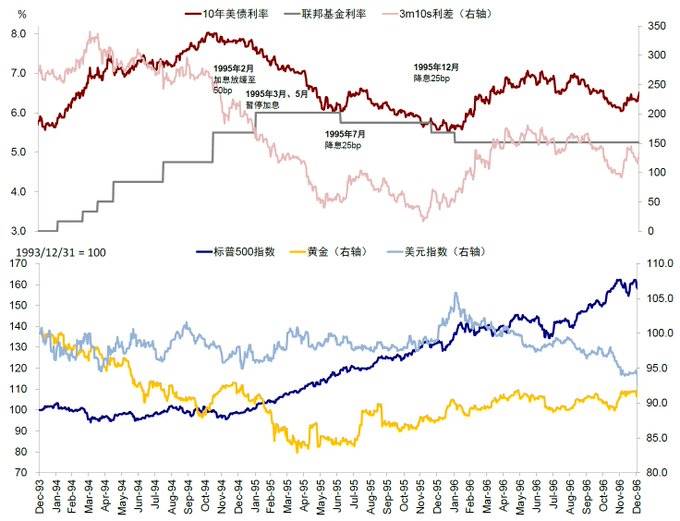

The third short cycle (1992-2000): The Clinton administration, which came to power in 1992, balanced the fiscal deficit by raising taxes and cutting spending. However, the friendly post-war economic development environment and good economic development expectations enhanced the financing willingness of residents and the corporate sector, and promoted the increase in the social leverage ratio. Since then, the economy has expanded and inflation has resumed its upward trend. In February 1994, the Federal Reserve began to raise interest rates for six consecutive times, a total of 3 percentage points to 6%. In December 1994, due to the Federal Reserve's six consecutive interest rate hikes that year, the increase in short-term interest rates significantly exceeded the increase in long-term interest rates, and the bond yield curve inverted. From the beginning of 1994 to mid-September, the U.S. bond market lost $600 billion in value, and the global bond market lost $1.5 trillion throughout the year. This is the famous 1994 bond crash.

Then the Asian financial crisis broke out in 1997 and the Russian debt crisis broke out in 1998, which directly led to the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), one of the four largest hedge funds in the United States, overnight. On September 23, Merrill Lynch and Morgan acquired and took over LTCM. In order to prevent financial market fluctuations from hindering US economic growth, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 50bps in the third quarter of 1998, and the enthusiasm for the development of Internet companies continued to rise. The incremental leverage ratio of the non-government sector continued to increase, among which the incremental leverage ratio of enterprises reached the highest value since 1986, driving the incremental leverage ratio of the society upward.

In 2000, the Internet bubble burst and the Nasdaq fell 80%. After the Internet bubble burst, the increase in non-government sector leverage and GDP growth rate both fell significantly, the increase in social leverage ratio turned negative, the scale of leverage ratio fell, the economy declined, inflation fell, and the next round of credit easing and economic recovery was triggered. Since then, this round of debt cycle has come to an end.

After the financial crisis in 2008, the unemployment rate in the United States reached 10%, and global interest rates fell to 0%. The economy could no longer be stimulated by lowering interest rates. The Federal Reserve launched the largest debt monetization by printing money to purchase debt. During the 12 years from 2008 to 2020, the United States launched the central bank's balance sheet expansion and bond purchases, which was essentially printing money, debt monetization and quantitative easing. Then, at the end of 21, it began to tighten to fight inflation. U.S. Treasury bond yields rose, the US dollar strengthened, and the Nasdaq index fell 33% from its high in 2021. At the same time, high interest rates also led to losses for the Federal Reserve.

After briefly reviewing a debt cycle, it was mentioned earlier that the United States is on the verge of a bubble burst. The transmission path of the big debt cycle is private sector-government-Federal Reserve. So what will happen when the big debt cycle reaches the central bank?

Step 1: The Fed expands its balance sheet to monetize debt

When a debt crisis occurs and interest rates cannot be lowered (for example, to 0%), money will be printed and bonds will be purchased. This process began in 2008, which is quantitative easing (QE). The United States has currently conducted four rounds of QE, buying a large number of U.S. Treasury bonds and MBS. The characteristic of QE is that the duration of the purchased assets is relatively long, which will forcibly lower the yield of Treasury bonds, prompting money to flow to risky assets and push up the prices of risky assets.

The money for QE here is realized through reserves (money that commercial banks deposit with the Federal Reserve). When the Federal Reserve buys bonds from banks, it does not need to spend money, but instead tells the banks that the Federal Reserve's reserves have increased.

Step 2: When interest rates rise, the central bank loses money

The Fed mainly has interest income and interest expenses. The structure of its balance sheet is to borrow short and buy long. Interest is paid on short-term assets such as RRP and Reserve, and interest is collected through relatively long-term assets such as US Treasuries and MBS. However, since the interest rate hike in 2022, the long-term and short-term interest rates have been inverted, so the Fed is losing money. In 2023, the Fed lost 114bn US dollars, and in 2024, it lost 82bn US dollars.

Previously, when the Federal Reserve made a profit, it handed over the profit to the Treasury Department. When it suffered a loss, this part became deferred assets (Earnings remittances due to the US Treasury), which has accumulated to more than 220 billion US dollars.

Step 3: When the central bank's net assets are significantly negative, it enters a death spiral

If the Fed keeps losing money, it will eventually end up with a significantly negative net worth, which is a real danger sign. This signals a death spiral, where rising interest rates cause creditors to see a problem and sell off debt, which causes interest rates to rise further, which causes further debt and currency sales, and the final result is a devaluation of the currency, leading to stagflation or depression.

At this step, the Fed faces the need to maintain loose policies to support the weak economy and fiscally weak government on the one hand, and tighten policies (high interest rates) to prevent the market from selling currency on the other hand.

Step 4: Deleveraging, debt restructuring and devaluation

When the debt burden becomes too great, a massive restructuring and/or devaluation occurs, which significantly reduces the size and value of the debt. At the same time, the currency depreciates, and holders of the currency and debt suffer a significant loss of real purchasing power until a new monetary system is established that is sufficiently credible to attract investors and savers to hold the currency again. At this stage, governments often implement extraordinary policies such as extraordinary taxes and capital controls.

Step 5: Return to balance and establish a new cycle

When the debt is devalued and the cycle comes to an end, the Federal Reserve may strictly implement the transition from a rapidly depreciating currency to a relatively stable currency by pegging the currency to hard currency (such as gold) under conditions of very tight monetary policy and very high real interest rates. In other words, a new cycle system is established.

Through the above steps, we can basically judge that the United States is now in the middle of the second step (central bank losses) to the third step (central bank net assets are significantly negative, entering a death spiral). So what is the next response of the Federal Reserve?

There are usually two ways to control debt. One is financial repression, which is essentially to lower interest costs. The other option is to control finance, that is, to reduce non-interest deficits. Lowering interest costs means lowering interest rates to ease the pressure of interest expenditures. There are only two ways to reduce non-interest deficits: one is to cut spending, and the other is to increase taxes. The Trump administration has been actively promoting these two methods. The DOGE government efficiency department has reduced government fiscal expenditures, and the tariff policy has increased government revenue.

Although Trump has already started his aggressive actions, the global financial market is not so convinced. Major central banks around the world have already started to buy gold. Now gold is second only to the US dollar and the euro, and has surpassed the Japanese yen to become the world's third largest reserve currency.

There is a serious problem with the current fiscal situation in the United States - borrowing new debt to repay old debt, but filling the fiscal gap by issuing bonds, and these new debts bring higher interest expenses, which has put the United States into a "vicious cycle of debt" and may eventually fall into the dilemma of "never being able to repay".

Under such circumstances, the dilemma of U.S. debt cannot be solved in a short time. In the end, it still has to be dealt with according to the two paths of the debt crisis mentioned above. Therefore, the Federal Reserve will choose to lower interest costs and ease the pressure of interest expenditures. Although interest rate cuts cannot fundamentally solve the debt problem, they can indeed temporarily alleviate some of the pressure of interest payments and give the government more time to deal with the huge debt burden.

The interest rate cut is actually highly consistent with Trump's "America First" policy. The current market unanimously believes that the tariffs and fiscal policies after Trump takes office will cause the US deficit to spiral out of control, leading to a decline in US credit, inflation and rising interest rates. In fact, the rise in the US dollar is due to the fact that market interest rates in other countries have fallen more than in the United States (countries with relatively high interest rates have seen currency appreciation). The decline in US Treasury prices (i.e., an increase in yields) is also a normal short-term rebound during a downward interest rate cycle.

As for the market's expected re-inflation, unless Trump triggers a fourth oil crisis, no logic can explain why he wants to push up the inflation level that Americans hate the most.

As for why the interest rate cut has been so difficult to implement, the expectations for interest rate cuts have been fluctuating constantly and repeatedly since the beginning of this year. I think it is because the expectation of interest rate cuts does not want to be overdrawn. Only the current "hawkish" policy can provide space for subsequent "cuts".

Looking back at the historical experience since 1990, the Fed paused its rate cuts in August 1989 and August 1995 respectively, in order to assess the subsequent growth situation and decide the speed and intensity of rate cuts. For example, after the "preventive" rate cut in July 1995, the Fed remained on hold for three consecutive meetings until the US government shut down twice due to failure to reach an agreement on the budget for the new fiscal year, and then decided to cut interest rates by another 25bp in December 1995.

Therefore, we should not follow the market thinking to make inferences, as there will often be problems. We should "think the opposite and do the opposite". So what are the subsequent opportunities?

1. From the perspective of US dollar assets, gold is still a relatively good asset; US bonds, especially long-term bonds, are very poor assets

2. At some point in time, the United States will actively or passively begin to cut interest rates. We should make good predictions and preparations and keep a close eye on the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield.

3. Bitcoin is still a high-quality investment target among risky assets, and its value remains strong.

4. Once the U.S. stock market experiences a large-scale correction, buy in batches on dips; technology stocks still have a high return ratio.