-

PA一线 · 25 分钟前

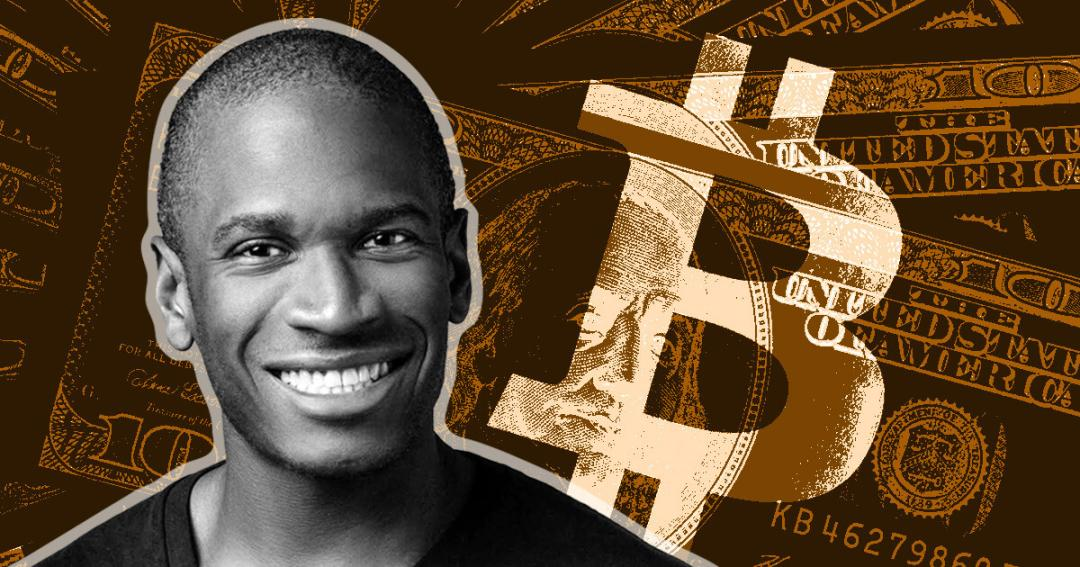

Solana联创Stephen Akridge遭前妻起诉,被指控窃取SOL质押收益

PA一线 · 25 分钟前

Solana联创Stephen Akridge遭前妻起诉,被指控窃取SOL质押收益Solana 联合创始人 Stephen Akridge 被其前妻 Elisa Rossi 起诉,指控他窃取了SOL 质押所产生的“数百万美元”奖励,并寻求包括违约、不当得利和欺诈在内的索赔。根据诉状,Stephen Akridge “利用了自己在加密货币和区块链方面的专业知识的巨大差异”,偷偷获取了 Elisa Rossi 的质押奖励。尽管 Elisa Rossi 在向法院提出的对诉讼部分内容保密的请求中提到了“巨额金额”,但诉讼中涉案代币的价值并未透露。Elisa Rossi 表示,从 3 月初到 5 月中旬,这些账户“一直由 Stephen Akridge 操作和控制。

-

PA一线 · 1 小时前

VolatilityShares申请推出基于Solana期货的杠杆型ETF

PA一线 · 1 小时前

VolatilityShares申请推出基于Solana期货的杠杆型ETFThe ETF Store 总裁 Nate Geraci 发推表示,Volatility Shares 向美国 SEC 提交了基于 Solana 期货的交易型开放式指数基金(ETF)申请,覆盖 1x、2x 和 -1x 杠杆敞口。VolatilityShares 曾积极推动 SEC 推出以太币期货 ETF。

-

链捕手 ChainCatcher · 1 小时前

各机构的2025年加密预测陆续出炉,去年他们的预测准确性如何?

链捕手 ChainCatcher · 1 小时前

各机构的2025年加密预测陆续出炉,去年他们的预测准确性如何?预测是一场智力与眼光的较量,市场则用无情的现实给出了答案。准备好,一起来看看这一年的加密江湖吧!

-

PA一线 · 1 小时前

Galaxy Research年度预测:BTC将在上半年突破15万美元,ETH将超5500美元

PA一线 · 1 小时前

Galaxy Research年度预测:BTC将在上半年突破15万美元,ETH将超5500美元Galaxy Research 发布 2025 年预测报告,涵盖比特币和以太币价格、DOGE、稳定币、DeFi、L2s、政策、VC 等。

PA一线 · 1 小时前

美国国税局要求DeFi经纪商2027年起报告数字资产销售收益并收集用户交易信息

PA一线 · 1 小时前

美国国税局要求DeFi经纪商2027年起报告数字资产销售收益并收集用户交易信息美国国税局(IRS)已最终确定规则,要求 DeFi 经纪商报告数字资产销售的总收益,并向客户提供 1099 表格,收集用户交易信息,包括姓名和地址。财政部指出,最终规则适用于“直接与客户”互动的“前端服务提供商”,这意味着运行用于访问去中心化协议的主要网站的实体,而不是协议本身。根据文件,该规则预计将于 2027 年 1 月 1 日或之后生效。加强数字资产服务提供商税收执法力度的想法首次出现在 2021 年通过的《基础设施投资与就业法案》中,以帮助支付该法案授权的支出。

-

Odaily星球日报 · 2 小时前

被华尔街“驯服”的比特币,最终会变成另一种美股?

Odaily星球日报 · 2 小时前

被华尔街“驯服”的比特币,最终会变成另一种美股?比特币和美股之间的相关性在逐渐增强。

-

PA一线 · 12 小时前

黑山司法部长签署引渡令,Do Kwon将被引渡至美国

PA一线 · 12 小时前

黑山司法部长签署引渡令,Do Kwon将被引渡至美国据黑山司法部声明,司法部长Bojan Božović已签署决定,将Terraform Labs创始人Do Kwon引渡至美国。同时拒绝了韩国的引渡申请。

-

PA一线 · 12 小时前

OpenAI计划调整结构,打造更强大的非盈利机构

PA一线 · 12 小时前

OpenAI计划调整结构,打造更强大的非盈利机构OpenAI宣布其董事会正在评估公司结构,将现有的营利部门转型为特拉华公共利益公司(PBC),以平衡股东、利益相关者和公共利益需求,同时为非盈利部门提供更强资源支持。

-

链上达人 · 12 小时前

AI平台Kaito走红,哪些热门项目将与之合作?

链上达人 · 12 小时前

AI平台Kaito走红,哪些热门项目将与之合作?未来会有越来越多的大项目拥抱Kaito,根据各自的榜单筛选贡献者并进行空投。

-

PA一线 · 13 小时前

柬埔寨央行批准合规稳定币服务,但仍禁用比特币

PA一线 · 13 小时前

柬埔寨央行批准合规稳定币服务,但仍禁用比特币柬埔寨国家银行(NBC)宣布允许商业银行和支付机构提供与稳定币和资产支持型加密货币相关的服务,但比特币等无支持资产仍被禁止。新规要求机构获得批准后才能开展加密资产兑换、转账及托管服务,同时禁止使用客户资产。

- 加密流通市值(7d)$3,425,028,664,759Market Cap恐惧贪婪指数(近30天)

白话区块链 · 13 小时前

美国“比特币战略储备”最快何时能落地?这几个时间点值得重点关注

白话区块链 · 13 小时前

美国“比特币战略储备”最快何时能落地?这几个时间点值得重点关注自11月初特朗普胜选“定局”以来,加密市场特别是比特币进入了强烈的“美国比特币战略储备”预期。

-

LBank · 14 小时前

LBank Pulse Focus专访:“新迷因教父”Murad揭秘2025年Memecoin超级周期的未来

LBank · 14 小时前

LBank Pulse Focus专访:“新迷因教父”Murad揭秘2025年Memecoin超级周期的未来Murad Mahmudov,作为这一趋势的见证者与分析者,提出了“Meme币超级周期”的概念。在他看来,Meme币不仅仅是一个纯粹的投机工具,而是加密世界中最强有力的用户普及引擎。他深入分析了Meme币成功的关键因素,并详细阐述了如何通过社交媒体和社区力量推动这些项目的成长。

-

PA一线 · 15 小时前

Bitget将销毁价值超50亿美金的BGB,占总供应量40%

PA一线 · 15 小时前

Bitget将销毁价值超50亿美金的BGB,占总供应量40%Bitget团队发布新版BGB白皮书,宣布引入回购销毁机制。首次将销毁核心团队持有的8亿枚BGB,BGB总供应量将减少为12亿,且100%全流通。随后,Bitget每季度利润的20%对BGB进行回购销毁。

-

链捕手 ChainCatcher · 15 小时前

2024年加密现货ETF成绩单:1 年,400亿美元

链捕手 ChainCatcher · 15 小时前

2024年加密现货ETF成绩单:1 年,400亿美元2024 年是加密资产真正转向主流资产的一年,本文将回顾今年加密现货 ETF 的关键里程碑,详细分析这一年来加密 ETF 的市场表现,并展望 2025 年加密 ETF 发展前景。

-

PA日报 · 16 小时前

PA日报 | Xterio将于2025年1月8日进行TGE;Matrixport称2025年比特币牛市可能面临多种潜在风险因素

PA日报 · 16 小时前

PA日报 | Xterio将于2025年1月8日进行TGE;Matrixport称2025年比特币牛市可能面临多种潜在风险因素Binance Alpha新增arc、WHY、APU、HAPPY和FWOG;1.69万亿枚BONK已完成销毁;BNSOL超级质押将上线第三期项目MANTRA(OM)。

-

Meta Era · 16 小时前

从星星之火到燎原之势,2024香港Web 3.0大事记

Meta Era · 16 小时前

从星星之火到燎原之势,2024香港Web 3.0大事记香港自 2022 年点燃 Web 3.0 星星之火,如今越烧越旺,已渐有燎原之势。纵观 2024 年 Web 3.0 在香港的发展,在搭建更稳定、更便利市场环境的同时,也在发挥其一直以来作为金融中心的优势。

-

PA一线 · 16 小时前

国家外汇管理局发布针对虚拟货币非法跨境金融活动等高风险交易的报告管理办法

PA一线 · 16 小时前

国家外汇管理局发布针对虚拟货币非法跨境金融活动等高风险交易的报告管理办法《银行外汇风险交易报告管理办法(试行)》已发布并自即日起施行。《办法》是《银行外汇展业管理办法(试行)》的配套文件,旨在强化银行外汇风险管理,对涉嫌虚假贸易、地下钱庄、虚拟货币非法跨境金融活动等高风险交易进行早识别、早预警和早处置。

-

PA图说 · 16 小时前

年终盘点系列丨波澜曲折,一图回顾光辉2024 🪶👇

PA图说 · 16 小时前

年终盘点系列丨波澜曲折,一图回顾光辉2024 🪶👇这一年加密行业在质疑与波折中成长

-

PA一线 · 16 小时前

币安:BNSOL超级质押将上线第三期项目MANTRA(OM)

PA一线 · 16 小时前

币安:BNSOL超级质押将上线第三期项目MANTRA(OM)据币安公告,BNSOL超级质押将于2025年1月1日8:00至2月1日7:59(北京时间)上线第三期项目MANTRA(OM)。OM APR Boost空投奖励于2025年01月02日起每日13:30(东八区时间) 左右可领取。

-

吴说区块链 · 16 小时前

Arthur Hayes最新播客全文:谈特朗普新政、比特币储备、投资策略与韩国市场

吴说区块链 · 16 小时前

Arthur Hayes最新播客全文:谈特朗普新政、比特币储备、投资策略与韩国市场尽管对美国政府直接采用 Bitcoin 储备持怀疑态度,Hayes 认为向数字资产的转型是不可避免的。

更多内容 Dec . 28

Dec.28