Since October this year, Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin has published a series of articles on the future possibilities of the Ethereum protocol, covering the six parts of the Ethereum development roadmap: The Merge, The Surge, The Scourge, The Verge, The Purge, and The Splurge. This article will interpret the first part of the roadmap (The Merge), explore what other technical designs of PoS can be improved, and how to achieve these improvements.

Vitalik believes that the "merge" refers to the most important event in the history of the Ethereum protocol since its launch: the transition from PoW proof of work to PoS proof of equity. Today, Ethereum has been a stable and running PoS system for nearly two years, and this proof of equity has performed very well in terms of stability, performance, and avoiding centralization risks. However, there are still some important areas for proof of equity to improve.

Ethereum’s 2023 roadmap breaks it down into several parts: improvements to technical features (such as stability, performance, and accessibility to smaller validators), and economic changes to address centralization risks. According to Vitalik, this article is not an exhaustive list of improvements to proof of stake, but more of an idea that is being actively considered.

The main objectives of the merger are as follows:

1. Single Slot Finality (SSF): Usually it takes about 15 minutes for an Ethereum block to be finalized. However, the time required for finalization can be significantly reduced by improving the efficiency of Ethereum's consensus mechanism to verify blocks. Blocks can be proposed and finalized in the same time slot without waiting for 15 minutes.

2. Confirm and complete transactions as quickly as possible while maintaining decentralization

3. Improve the feasibility of staking for individual stakers

4. Improve robustness

5. Improve Ethereum’s resistance and recovery capabilities to 51% attacks (including finality reversal, finality blocking, and censorship)

Single-slot finality and the democratization of staking

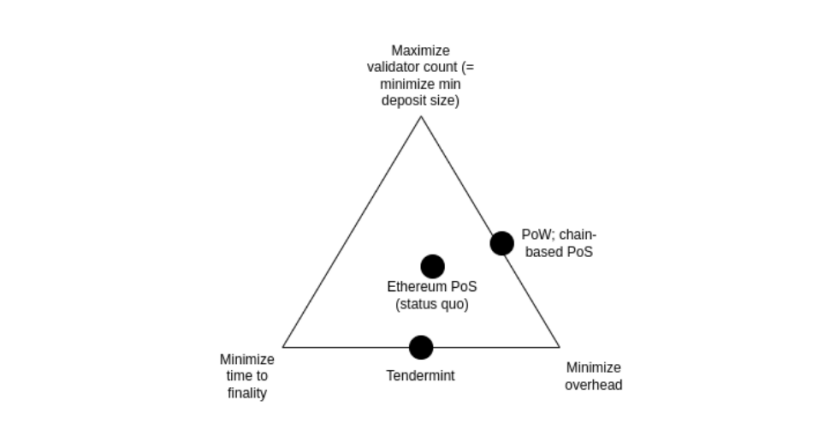

Currently, it takes 2-3 epochs (about 15 minutes) to complete a block, and 32 ETH is required to become a staker. This was originally a compromise to strike a balance between three goals:

- Maximize the number of validators participating in staking (minimize the ETH required for staking);

- Minimize finality time;

- Minimize the overhead of running a node.

These three goals are in conflict with each other: in order to achieve economic finality (i.e. an attacker needs to destroy a large amount of ETH to revert a finalized block), every validator needs to sign two messages for each finalization. Therefore, if there are a large number of validators, it will either take a long time to process all the signatures, or require very powerful nodes to process all the signatures at the same time.

It all hinges on one key goal of Ethereum: ensuring that even a successful attack is costly for the attacker. This is what the term “economic finality” means.

There are counter-examples, and blockchains that do not have "economic finality" (such as Algorand) solve this problem by randomly selecting a committee to finalize each time slot. But the problem with this method is that if the attacker does control 51% of the validators, the cost of the attack is extremely low: only some of the nodes in the committee will be detected as participating in the attack and punished. This means that the attacker can repeatedly attack the chain many times.

Therefore, if Ethereum wants to achieve economic finality, a simple committee-based approach will not work, and participation of the full set of validators is required.

Ideally, Ethereum would like to improve on the status quo in two ways while preserving economic finality:

1. Finalize blocks in one slot (ideally, keep or even reduce the current length of 12 seconds) instead of 15 minutes

2. Allow validators to stake with 1 ETH (from 32 ETH to 1 ETH)

The first ensures that all Ethereum users benefit from the higher level of security achieved through finality. Today, most users cannot enjoy this security because they are unwilling to wait 15 minutes; with single-slot finality, users can see the finalization of transactions almost immediately after the transaction is confirmed. Second, if users and applications do not have to worry about the possibility of chain rollbacks, then it simplifies the protocol and the surrounding infrastructure.

The second point is to support solo stakers. According to multiple polls, the main factor that prevents solo staking is the 32 ETH minimum. Lowering the minimum to 1 ETH will solve this problem.

There is a challenge here: both the goals of faster finality and more democratized staking conflict with the goal of minimizing overhead. In fact, this fact is why Ethereum did not adopt single-slot finality in the first place. However, recent research has suggested some possible solutions to this problem.

Working principle:

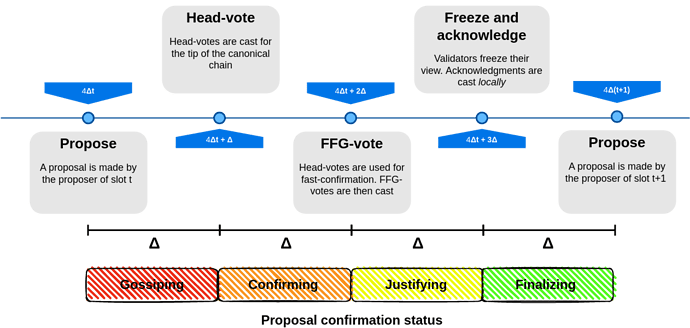

Single-slot finality involves using a consensus algorithm that finalizes blocks within one slot. This is not a difficult goal in itself, and many algorithms (such as Tendermint consensus) already achieve this.

A desirable property unique to Ethereum is inactivity leaks: this property allows the blockchain to continue functioning and eventually recover even if more than 1/3 of validators are offline.

Single-slot deterministic proposal

There are several leading solutions to the problem of how to make single-slot finality work at very high validator counts without incurring extremely high node operator overhead:

Option one is to brute force and implement a better signature aggregation protocol, possibly using ZK-SNARKs, which would make it possible to process signatures from millions of validators in a single time slot. For example, Horn is one of the proposals put forward to design a better aggregation protocol.

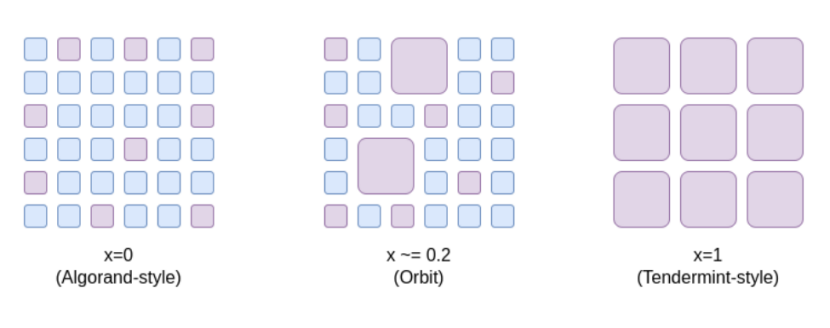

Option two is the Orbit committee, a new mechanism that allows randomly selected medium-sized committees to be responsible for chain finality, but retains attack cost characteristics. Orbit exploits pre-existing heterogeneity in validator deposit sizes to achieve the largest possible economic finality while still giving small validators a matching role.

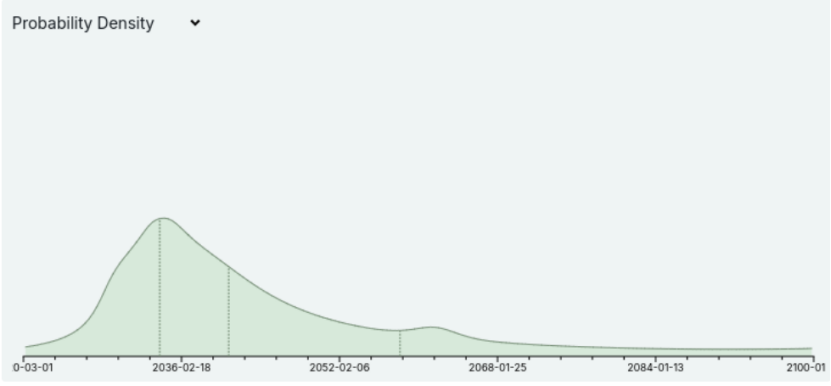

As shown in the figure below, between the range x = 0 (Algorand committee, no economic finality) to x = 1 (Ethereum’s status quo) — Orbit SSF carves out a middle ground:

1. The cost of doing evil is still very high, which ensures extreme security;

2. But at the same time, only a medium-sized random sample of validators is required to participate in each time slot, reducing the burden on nodes.

Option three is dual staking, a mechanism with two classes of stakers, one with a higher deposit requirement and the other with a lower deposit requirement. Only the tier with the higher deposit requirement will directly participate in providing economic finality. Various proposals have been made as to what the responsibilities of the lower tier deposits should be, including:

- The right to delegate stake to a more senior stakeholder;

-Randomly select low-level stakers to attest and finalize each block;

-Generate rights for inclusion in lists, etc.

As for Ethereum’s security experience and staking centralization, each solution has its pros and cons and trade-offs: brute force cracking can solve the problem, but it requires aggregating a large number of signatures in a very short period of time, which is technically very difficult; the Orbit Committee needs to verify its security and features, and formalize and implement them; the two-layer staking mechanism faces centralization risks, which largely depend on the specific rights obtained by the low-staking layer.

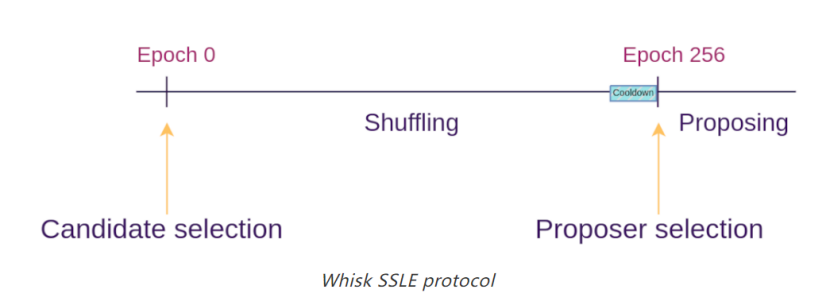

In addition to single-slot finality, single secret leader election is also an important issue in Ethereum’s proof-of-stake system. Today, it is known in advance which validator will propose the next block, which creates a security vulnerability where an attacker can monitor the network, determine which validators correspond to which IP addresses, and launch a DoS attack on the validator when it is about to propose a block.

The best way to solve this problem is to hide the information about which validator will generate the next block, at least until the block is actually generated.

Single secret leader election

Currently, it is known in advance which validator will propose the next block, which creates a security vulnerability: an attacker can monitor the network, determine which validators correspond to which IP addresses, and launch a DoS attack on the validator when it is about to propose a block.

The single secret leader election protocol solves this problem by using some cryptographic techniques to create a “blind” validator ID for each validator, and then giving many proposers the opportunity to shuffle and re-blind the pool of blinded IDs.

However, implementing a sufficiently simple single secret leader election protocol is non-trivial.

The simplicity of the Ethereum protocol is paramount, and we do not want to add further complexity. Simplified SSLE using ring signatures is only a few hundred lines of specification code and introduces new assumptions in complex cryptography.

There is also the question of how to achieve sufficiently efficient quantum-resistant SSLE. It may eventually be the case that the “marginal additional complexity” of SSLE will only drop to a sufficiently low level if we dare to try for other reasons and introduce a mechanism for performing general zero-knowledge proofs in the Ethereum protocol at L1.

In addition, faster transaction confirmation is also one of the problems that the Ethereum proof-of-stake system needs to solve.

There is value in further reducing Ethereum’s transaction confirmation time (from 12 seconds to 4 seconds). Doing so would significantly improve the user experience of L1 and rollups while making DeFi protocols more efficient. It would also make L2 more decentralized as it would allow a large number of L2 applications to operate on rollups, reducing the need for L2 to build its own committee-based decentralized ordering.

There are two general techniques: reducing the slot time to 8 seconds or 4 seconds; allowing proposers to issue pre-confirmations during a single slot. However, it is not clear how feasible it is to shorten the slot time.

Even today, it is difficult for stakers in many parts of the world to get attestations fast enough. The 4 second slot time attempt risks validator centralization, and latency makes becoming a validator outside of a few geographically advantageous regions impractical.

The weakness of the proposer preconfirmation approach is that it can greatly improve the average inclusion time, but not the worst case. In addition, there is an open question of how to incentivize preconfirmation.

In the face of possible future quantum computing threats, Ethereum needs to actively develop quantum-resistant alternatives. Every part of the Ethereum protocol that currently relies on elliptic curves needs to have some hash-based or other quantum-resistant alternative. This justifies the conservatism in the performance assumptions around proof-of-stake design and is a reason to more actively develop quantum-resistant alternatives.

summary

The Ethereum proof-of-stake system is full of challenges on the road of technological evolution. Due to the high threshold for Ethereum staking alone, staking service providers led by Lido have become the first choice for Ethereum node staking, and the two-layer staking solution also has a certain degree of centralization risk. In order to meet these challenges, single-slot finality and staking democratization, single secret leader election, faster transaction confirmation, and the development of quantum attack-resistant alternatives are all important issues that Ethereum needs to deal with.

Vitalik gave a comprehensive consideration to the “The Merge” upgrade and proposed as many technical solution combinations as possible. He discussed the design potential of Ethereum’s PoS technology and the currently possible technical upgrade paths.

In the process of technological upgrading, Ethereum is still striving to continuously explore and innovate, weighing and choosing between different technical solutions to find the most suitable development path and achieve higher security, performance and decentralization.